Hospitalizations and healthcare costs associated with serious,non-lethal firearm-related violence and injuries in the United States,1998–2011

Jason L. Salemi, Vikas Jindal, Roneé E. Wilson, Mulubrhan F. Mogos, Muktar H. Aliyu, Hamisu M. Salihu

Hospitalizations and healthcare costs associated with serious,non-lethal firearm-related violence and injuries in the United States,1998–2011

Jason L. Salemi1, Vikas Jindal2, Roneé E. Wilson3, Mulubrhan F. Mogos4, Muktar H. Aliyu5, Hamisu M. Salihu1

Objective:To describe the prevalence, trends, correlates, and short-term outcomes of inpatient hospitalizations for firearm-related injuries (FRIs) in the United States between 1998 and 2011.

Methods:We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of inpatient hospitalizations using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. In addition to generating national prevalence estimates, we used survey logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between FRIs and patient/hospital-level characteristics. Temporal trends were estimated and characterized using joinpoint regression.

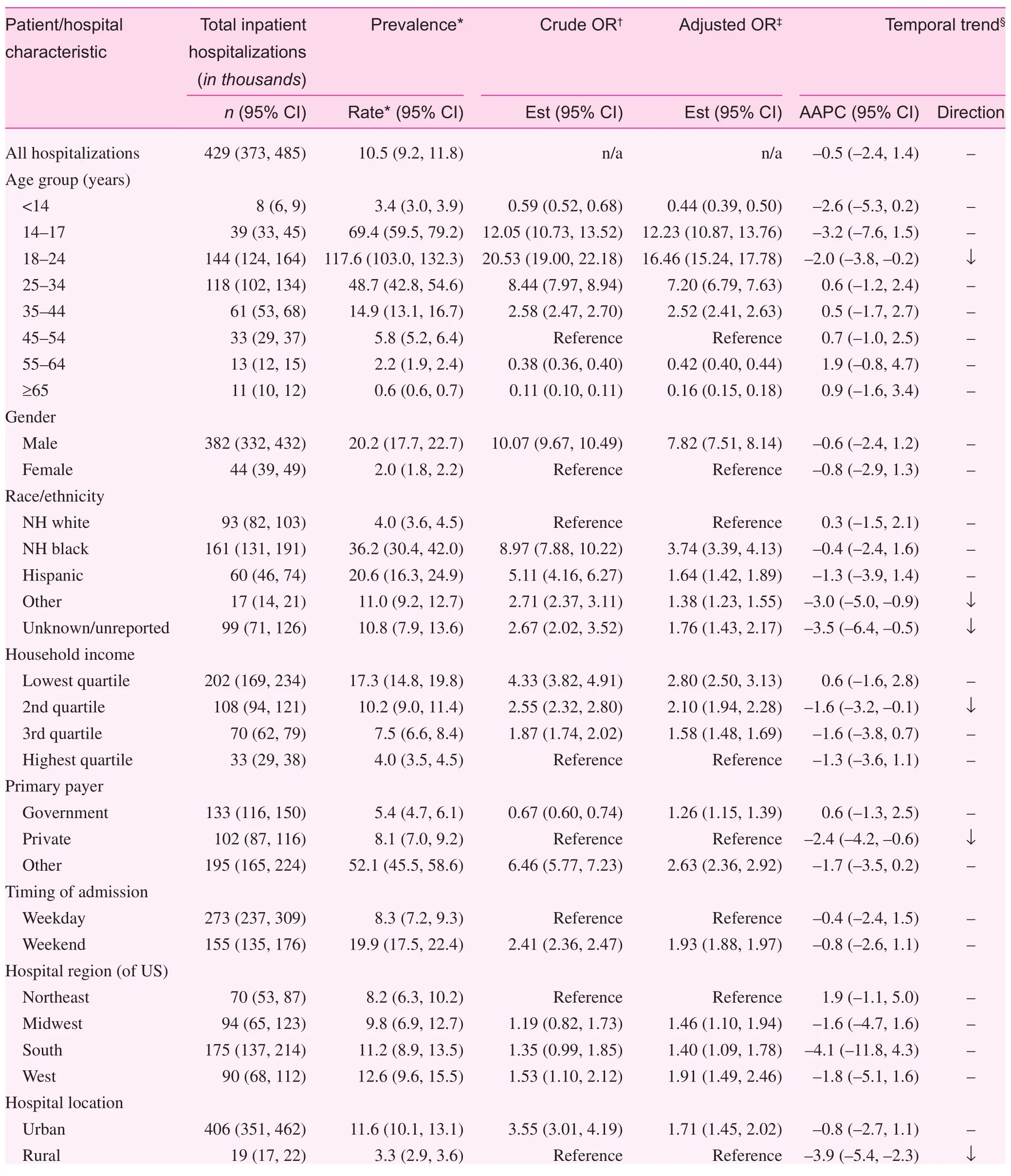

Results:There were 10.5 FRIs (95% CI: 9.2–11.8) per 10,000 non-maternal/neonatal inpatient hospitalizations, with assault accounting for 60.1% of FRIs, followed by unintentional/ accidental(23.0%) and intentional/self-inflicted FRIs (8.2%). The highest odds of FRIs, particularly FRIs associated with an assault, was observed among patients 18–24 years of age, patients 14–17 years of age, patients with no insurance/self-pay, and non-Hispanic blacks. The mean inpatient length of stay for FRIs was 6.9 days; however, 4.7% of patients remained in the hospital over 24 days and 1 in 12 patients (8.2%) died before discharge. The mean cost of an inpatient hospitalization for a FRI was $22,149, which was estimated to be $679 million annually; approximately two-thirds of the annual cost (64.7%) was for assault ($439 million).

Conclusion:FRIs are a preventable public health issue which disproportionately impacts younger generations, while imposing significant economic and societal burdens, even in the absence of fatalities. Prevention of FRIs should be considered a priority in this era of healthcare cost containment.

Assault; cost; gunshot; firearms; hospitalization; intentional injury

Introduction

Firearm-related injuries (FRIs) have long been a major public health concern. In 2013 alone,over 32,000 people in the United States (US)died as a result of a FRI (nearly 4 people every minute), including 193 children less than 15 years of age [1]. Despite the overwhelming attention on immediately fatal FRIs,there have been 43 non-fatal FRIs for every fatality since 2000 [2]. Most non-fatal FRIsresult in lengthy hospital stays, a diminished quality of life for the surviving victim, and considerable economic costs to society [3–5].

Although the frequency of FRIs in the US decreased precipitously between 1990 and 1999, the rate has plateaued during the 2000s [6]. There is little evidence, however, regarding a variation in FRI trends, short-term outcomes, or annual medical care expenditures over the past decade across sociodemographic and geographic subgroups, or in the underlying reasons for FRIs (e.g., assault, accident, or self-inflicted).Therefore, the primary aims of this study were as follows: (1)describe the frequency, prevalence, and temporal trends of inpatient hospitalizations for FRIs in the US between 1998 and 2011; (2) investigate individual- and hospital-level sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that are associated with FRIs and FRI subtypes; and (3) estimate indices of healthcare utilization, the costs of inpatient care, and in-hospital mortality among patients hospitalized for a FRI.

Methods

Study design and data source

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of inpatient hospitalizations in the US between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2011 using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). The NIS is part of a collection of healthcare databases created under the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), and it currently constitutes the largest all payer, publicly-available inpatient database in the US [7]. The NIS strati fies all non-federal community hospitals from participating states into groups according to the following five characteristics: geographic region of the US; urban location;rural location; number of beds; and type of ownership. Then,within each stratum, a 20% sample of hospitals is drawn using systematic random sampling to ensure unbiased geographic representation [7]. All inpatient hospitalization records from selected hospitals are included in the NIS, and HCUP provides discharge-level sampling weights so that national frequency and prevalence estimates take into account the two-stage cluster sampling design. The NIS contains approximately 7 million inpatient hospitalizations each year (36 million when weighted), and has grown from 22 participating states in 1998 to 46 in 2011.

Study population

In this study, we were interested in identifying inpatient hospitalizations associated with FRIs. Our definition of a firearm in this study included handguns, shotguns, hunting rifles,military firearms, and other/unspecified firearms; however,we did not consider air guns, paintball guns, or explosive devices as firearms. A hospitalization was considered to have occurred as a result of a FRI and was subsequently classified according to the manner/intent of the injury using the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision,Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) E-codes: E965.0-E965.4,E979.4 (assault); E922.0-E922.3, E922.8, E922.9 (unintentional); E955.0-E955.4 (intentional/self-inflicted); E970 (legal intervention); and E985.0-E985.4 (other or unknown manner/intent). For the small proportion of records that included codes for more than one manner/intent category (0.1%), the final classification was hierarchical, so that groups were mutually exclusive and did not have dual membership. Classification ordering was as follows: assault; accident; self-inflicted; and legal intervention. For example, if a discharge record had codes for both assault and legal intervention, it would be classified as assault. Discharge records without at least one of these codes were considered as a non-FRI hospitalization. We excluded discharge records, regardless of the presence of a FRI, in which the primary reason for admission was associated with pregnancy, childbirth, or the neonatal period. These were identified using major diagnostic categories 14 (“pregnancy, childbirth,and the puerperium”) and 15 (“newborns and other neonates with conditions originating during the perinatal period”), and using an HCUP-created variable that indicated neonatal and/or maternal diagnoses and procedures. The reason for the exclusion of maternal and neonatal discharge records was that these discharges represented nearly one-fourth (23.5%) of all inpatient discharges in the US between 1998 and 2011, but were much less likely to be at risk for a FRI (the discharges make up only 0.38% of all FRIs in the NIS). Therefore, we felt prevalence estimates would be more accurate by considering the rate of FRIs among non-maternal/neonatal inpatient discharges.

Individual- and hospital-level covariates

We used ICD-9-CM codes to ascertain other clinical details for each FRI hospitalization, including the type of firearm involved (e.g., handgun, shotgun, hunting rifle, or military firearm), the geographic location of the injury (home/ residential area vs. away from home), and the site of the injury (head,trunk, upper extremity, lower extremity, multiple sites, or unknown). We documented whether or not the patient had a mental illness, including adjustment, anxiety, disruptive behavior, impulse control, mood, personality, and psychotic disorders, or use/abuse of alcohol or illicit substances. For each discharge record, the NIS contains individual-level sociodemographic characteristics. The patient age in years was categorized as follows: <14; 14–17; 18–24; 25–34; 35–44;45–54; 55–64; and ≥65. Self-reported race/ethnicity was first stratified on ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic [NH]), and the NH group was further subdivided by race (white, black,or other). The primary payer was classified into government(Medicare/Medicaid), private (commercial carriers, and private HMOs and PPOs), and other, including self-pay and no charge. Using the patient’s residential zip code, HCUP provided quartiles of estimated median household incomes. We also considered several characteristics of the treating hospital, including US census region (northeast, mid west, south, or west), location (urban or rural), bed size (small, medium, or large), and teaching status (teaching or non-teaching).

Outcomes

We examined several short-term outcomes associated with hospitalization for a FRI. Length of stay (LOS) was used as a proxy for the level of healthcare utilization, and for the severity of complications resulting from the FRI. In addition to the mean LOS, we also considered the proportion of FRIs requiring a prolonged hospitalization, which was defined as a LOS≥95th percentile among all FRIs (>24 days in our sample).The NIS does not capture events beyond the current hospitalization; therefore, we were only able to assess in-hospital mortality or death before discharge. The cost of inpatient care associated with FRIs was estimated using the total hospital charges reported for the patient’s hospitalization. Unadjusted charges can be a misleading indicator because the markup from the cost for the hospital to provide services to what is ultimately charged varies significantly across hospitals, among different departments within the same hospital, and over time[8, 9]. To obtain a more accurate estimate of actual cost, we adjusted total charges as follows: (1) multiplied the reported charges by a year- and hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratio(CCR) obtained from HCUP; and (2) multiplied the amount from step 1 by a HCUP-generated “adjustment factor” (AF),which attempts to account for interdepartmental variations in markup within each hospital [10, 11]. The final formula estimating the direct cost of inpatient care for each hospitalization for FRI is presented below by the following equation:

total cost = total charges × year- and hospital-specific CCR × AF

Statistical analysis

We estimated the frequency and rate of inpatient hospitalizations for FRIs overall, for FRI subtypes, and by individual- and hospital-level characteristics. All discharges were weighted to account for the complex sampling design of the NIS and so that national estimates can be generated[7]. Temporal trends were estimated and characterized using joinpoint regression (JPR). JPR is useful in identifying changes in the temporal trends of events over time [12]. First,the JPR model fits annual rate data to a straight line (one with no “joinpoints”) that assumes a single trend can best characterize rates over the entire study period [13]. Then, a joinpoint is added to the model and a Monte Carlo permutation test is used to determine whether or not the joinpoint offers a statistically significant improvement to the model; if so,the joinpoint is incorporated. The process is repeated until a best fitting model, with an optimal number of joinpoints,is specified. In the final model, each joinpoint corresponds to a statistically significant change (increase or decrease) in the temporal trend, and an annual percent change (APC) is calculated to describe how the rate changes within that time interval. JPR also estimates the average APC (AAPC), which characterizes the trend over the entire study period, even when there are significant changes in the trend over time[13]. Because the NIS sampling design changed between 1998 and 2011, we incorporated HCUP-supplied NIS-trends files for our trend analyses so that trend weights and data elements were defined consistently over time [14].

Survey logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios(ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that represent the association between FRI and each patient- or hospital-level characteristic. We constructed a crude (unadjusted) model for each factor and two multivariable models. Selection of covariates for inclusion into each multivariable model was based on a review of the literature, data availability, and empirical bivariate analyses. The first multivariable model included all patient factors, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, primary payer, alcohol or substance use/abuse,and mental illness. The second multivariable model added timing of the admission and hospital region, location, and teaching status to the first model. In this paper, we present the results of the crude and second (best- fitting) multivariable model.

The mean LOS, in-hospital mortality rate, and costs associated with hospitalization for a FRI were calculated, followed by FRI and patient subgroup analyses. Our national prevalence and cost estimates were used to determine the total annual expenditures on inpatient care in the US caused by FRIs. To account for in flation, all cost estimates were adjusted to 2011 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index [15]. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and the JPR program (version 4.1.1.3) [12]. We assumed a 5% type I error rate for all hypothesis tests (two-sided). Because of the de-identified nature of NIS data, this study was classified as exempt by the Baylor College of Medicine and the University of South Florida Institutional Review Boards.

Results

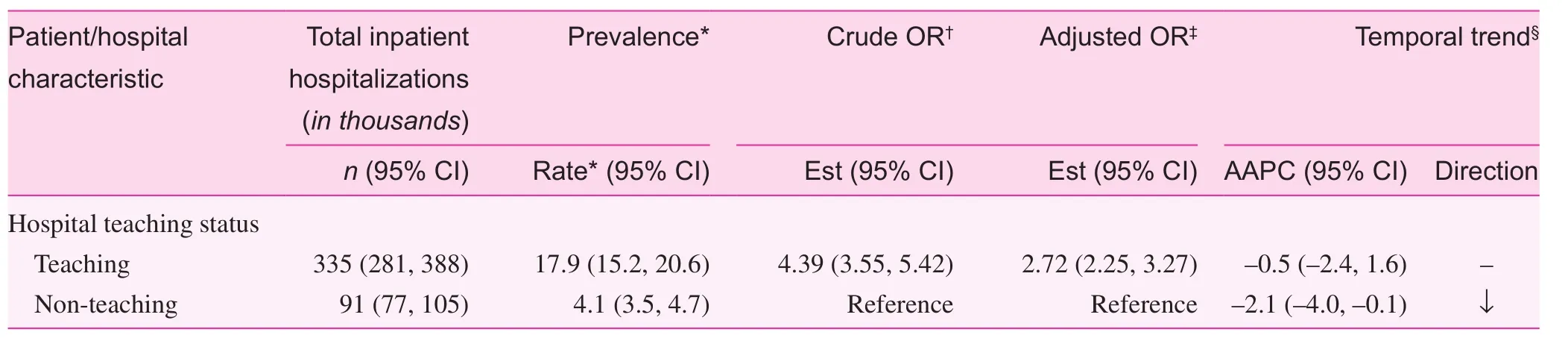

Between 1998 and 2011 there were an estimated 429,036 discharge records with a diagnosed FRI (an average of 30,645 per year) in the US, which corresponds to a rate of 10.5 FRIs(95% CI: 9.2–11.8) per 10,000 non-maternal/neonatal inpatient hospitalizations (Table 1). The most common documented manner/intent associated with FRIs was assault (60.1%),followed by unintentional/accidental (23.0%), intentional/self-inflicted (8.2%), and legal intervention (1.6%). Greater than 62% of discharge records were missing the specific type of firearm responsible for the injury; however, among the discharge records with documentation, handguns were implicated in over 76% of FRIs, with shotguns and hunting ri fles responsible for 17.7% and 5.4%, respectively. Although the overall rate of inpatient hospitalizations caused by FRIs decreased from 13.0 per 10,000 in 1998 to 9.5 per 10,000 in 2011, there was considerable annual fluctuation and no statistically significant temporal trend during the study period (Fig. 1, APC:–0.5; 95% CI: –2.3–1.4).

The associations between patient- and hospital-level characteristics and FRIs are presented in Table 1, in addition to subgroup-specific frequencies, rates, and trends. The highest rates of FRIs (per 10,000 hospitalizations) were observed among patients 18–24 years of age (117.6), patients 14–17 years of age(69.4), patients with no insurance/self-pay (52.1), NH-blacks(36.2), and patients with a substance abuse disorder (27.1).Except for children under 14 years of age, we observed a trend of decreasing odds of hospitalization for FRIs with increasing age (Ptrend<0.001). Males were nearly 8 times more likely than females to have a FRI hospitalization (95% CI: 7.5–8.1),and compared to NH whites, NH blacks and Hispanics had 3.7 (95% CI: 3.4–4.1) and 1.6 (95%: 1.4–1.9) higher odds of hospitalization for a FRI. There was a statistically significant trend of higher odds of FRIs with lower levels of household income (Ptrend<0.001); specifically, patients in the lowest versus highest quartile of income were 2.8 times more likely to be hospitalized for a FRI (95% CI: 2.5–3.1). There was considerable geographic variation, even after adjusting for population characteristics, with the western region of the US having the highest odds of hospitalization caused by a FRI. Teaching hospitals (OR=2.7; 95% CI: 2.3–3.3) and hospitals in urban areas (OR=1.7; 95% CI: 1.5–2.0) were more likely to have a FRI hospitalization, and FRIs were twice as common on the weekend compared to the weekday. Several subgroups, including the 18–24 year age group, patients with private insurance,patients residing in rural areas, and patients in the 2nd quartile of household income experienced statistically significant decreases in the rate of FRI hospitalizations during the study period, with APCs ranging from –1.6 to –3.9 (Table 1). All other subgroups experienced no significant rate changes over time; there were no increasing trends among any subgroup.

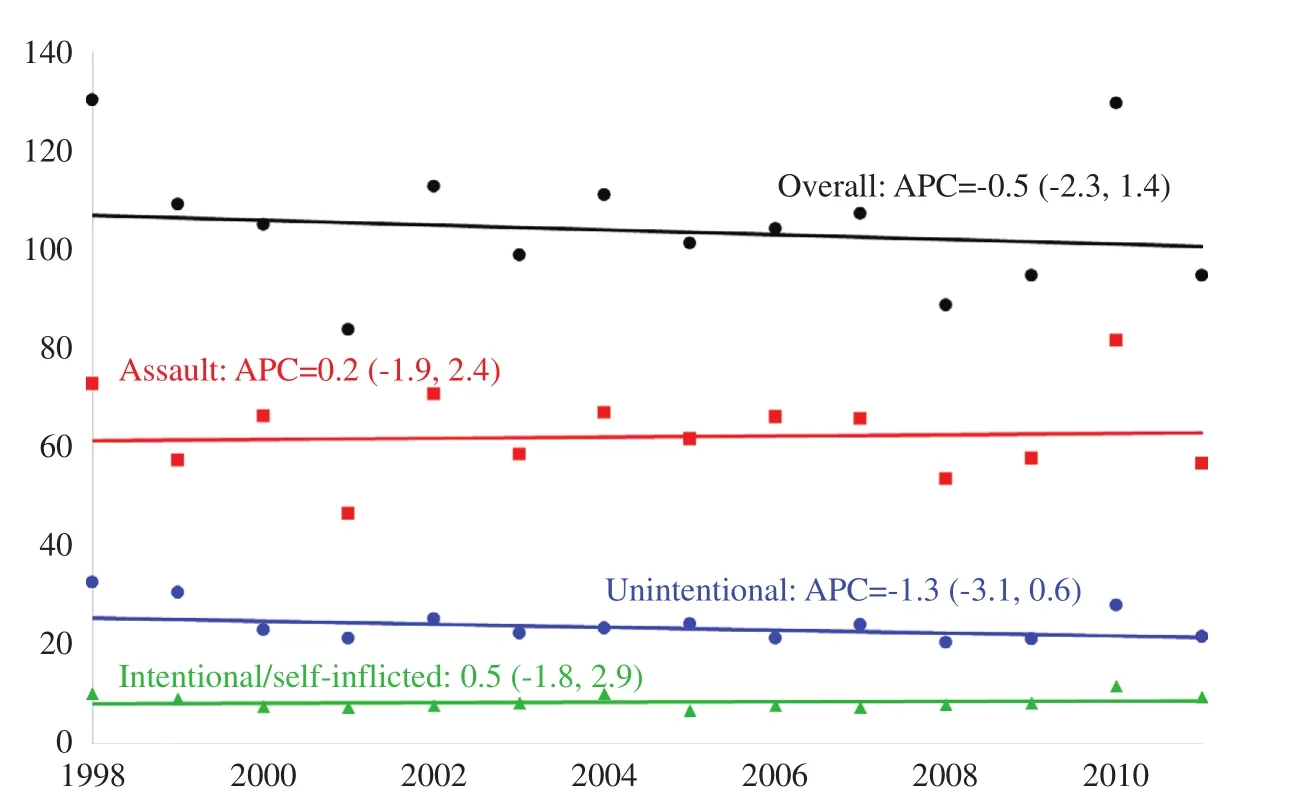

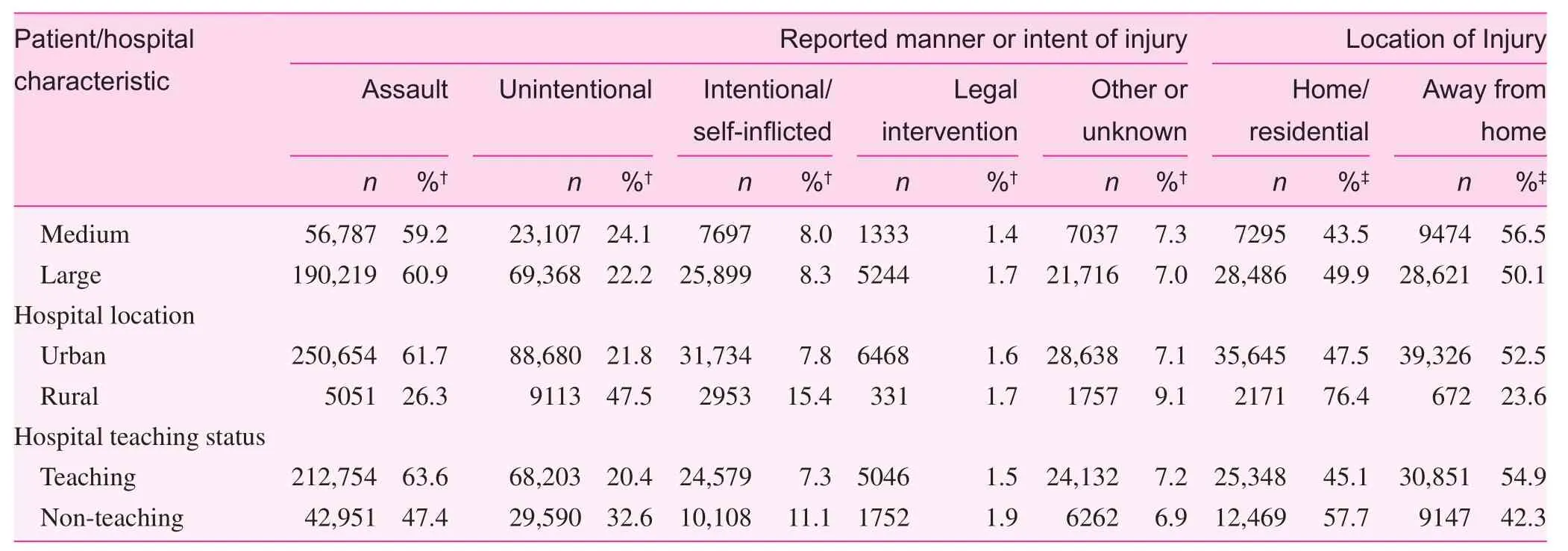

Table 2 describes the distribution of inpatient hospitalizations for FRIs by the reported manner or intent of injury and the geographic location in which the injury occurred. Assault was the intent of injury in 6 of every 10 FRI hospitalizations overall, and was more likely the reason for the FRIs among Hispanics (72.8%), NH blacks (70.8%), patients with lowerhousehold incomes, patients without private insurance, and patients 14–34 years of age. Compared with the overall proportion of FRIs that were accidental (23.0%), unintentional FRIs were particularly common among children under 14 years of age (49.6%), NH whites (34.0%), and patients residing in rural settings (47.5%). The proportion of FRIs that were self-inflicted increased markedly with increasing age (from 2.7%in the <14 year age group to 41.8% in the ≥65 year age group)and increasing income (5.9%–13.9%), and was particularly high among NH whites (23.1% compared to NH blacks andHispanics [1.5% and 3.4%, respectively]). Although the location of the injury was only listed in 1 of every 5 FRI hospitalizations, there was a near-even split among documented cases.Injuries were more likely to occur at home or in residential areas among young and old age extremes, females, NH whites,patients with higher household incomes, and patients residing in rural areas (Table 2).

Table 1. Frequency, prevalence, and temporal trends of inpatient hospitalizations for firearm-related injuries in the United States, by individual and hospital-level characteristics, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1998–2011.

Table 1. (continued)

Fig. 1. Trends in inpatient hospitalizations for major types of firearm-related injuries in the United States, Nationwide Inpatient Sample,1998–2011.

Table 2. Distribution of inpatient hospitalizations for firearm-related injuries in the United States*, by individual and hospital-level characteristics and by the manner/intent and geographic location of injury, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1998–2011.

Table 2. (continued)

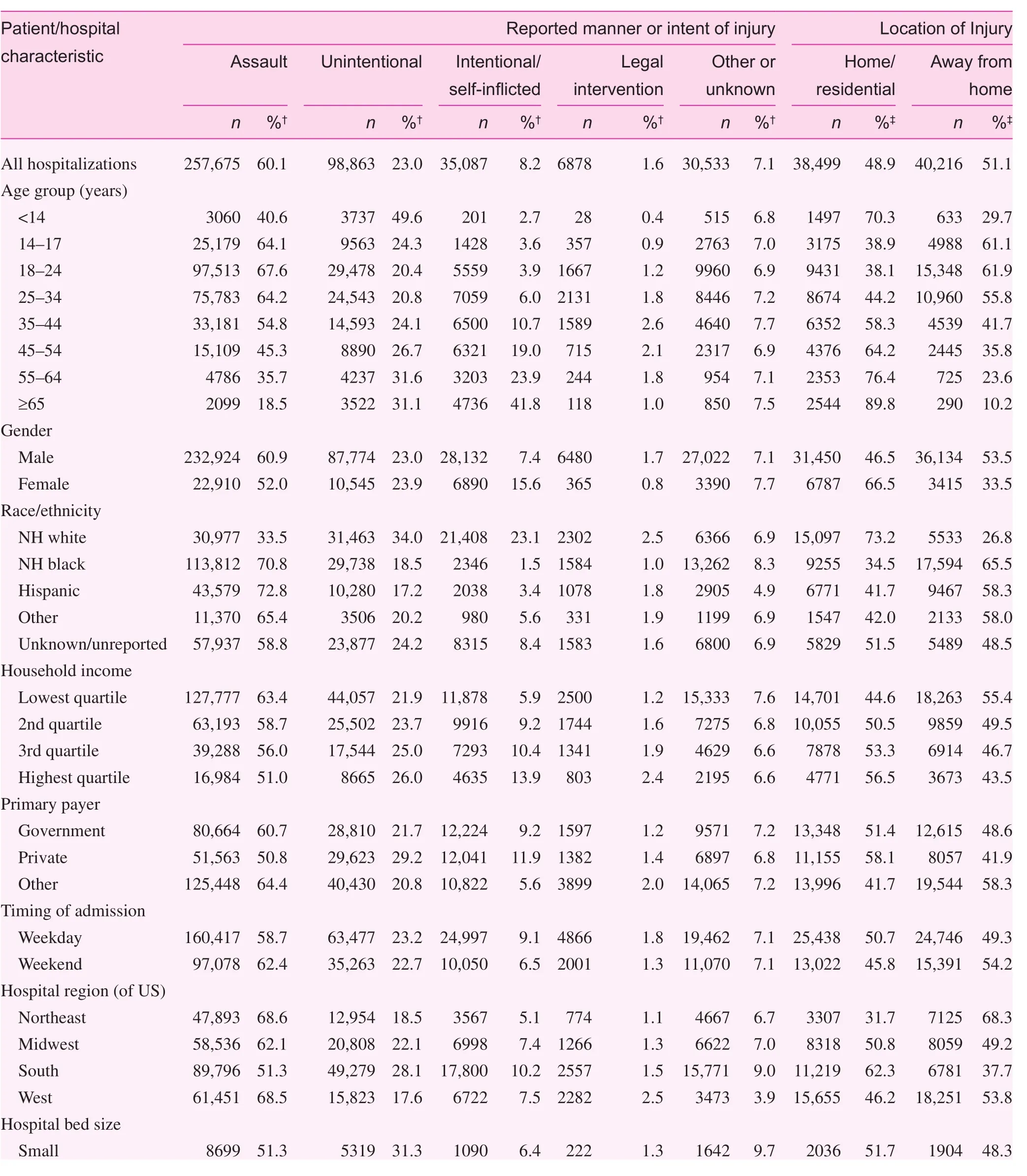

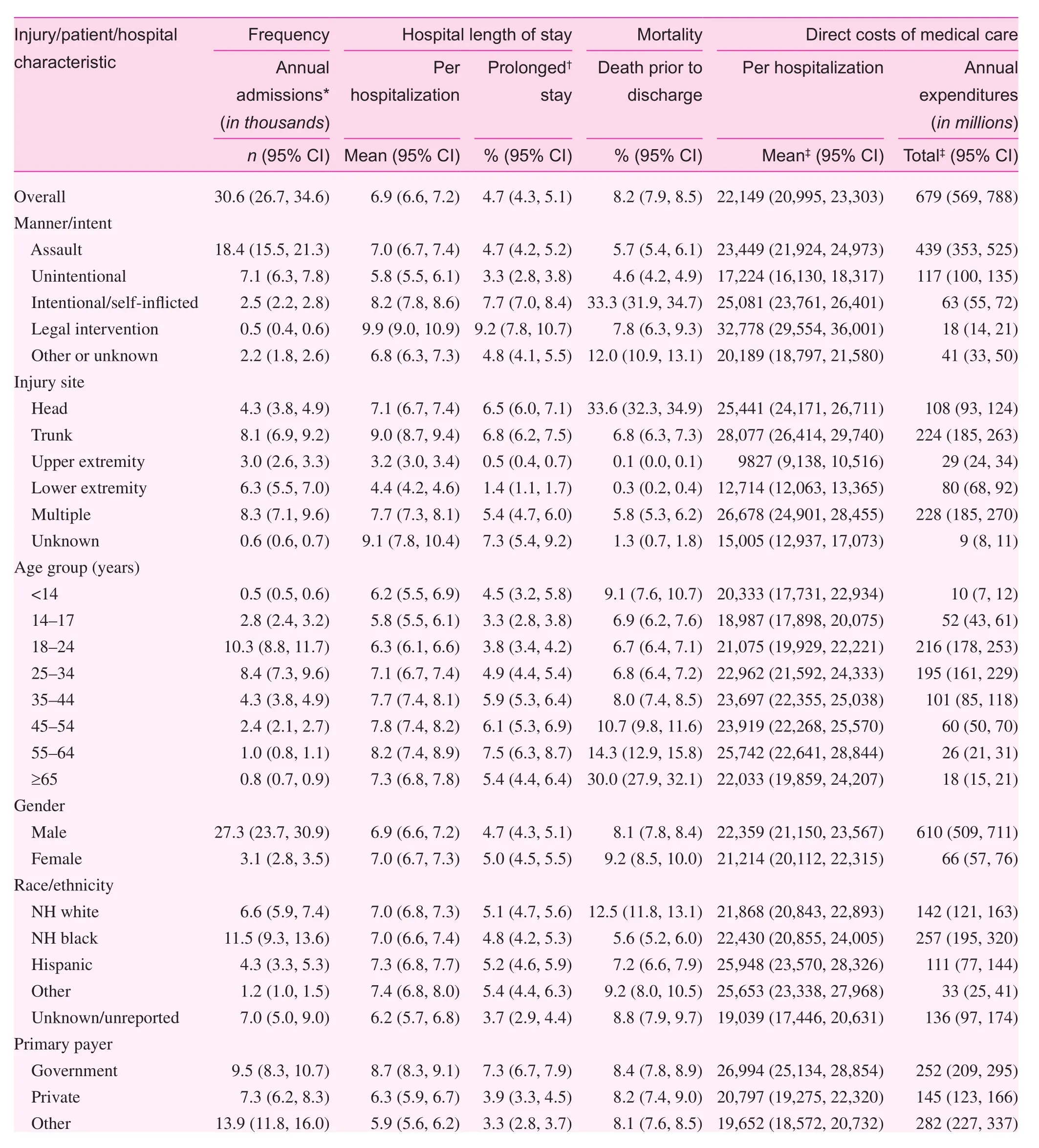

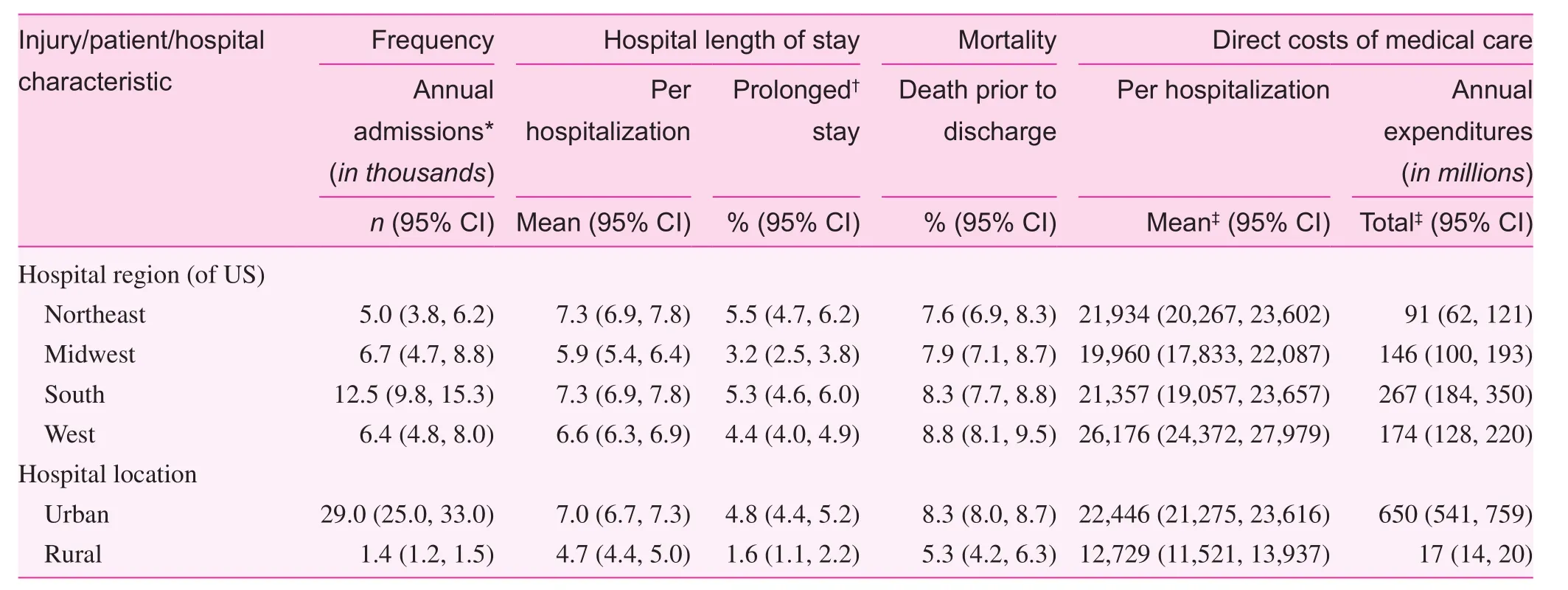

Hospital LOS, in-hospital mortality, and the direct costs of inpatient care that were associated with FRI hospitalizations are presented in Table 3. Overall, the mean inpatient LOS for FRIs was 6.9 days; however, 4.7% of patients remained in the hospital over 24 days and approximately 1 in 12 patients(8.2%) died before discharge. The mean cost of medical services provided during an inpatient hospitalization for a FRI was $22,149, which was estimated at more than $7.5 billion between 2001 and 2011 or $679 million annually. FRIs resulting from assault comprised 64.7% of annual expenditures on FRIs ($439 million), followed by 17.3% for unintentional injuries ($117 million), and 9.3% for intentional/self-inflicted FRIs ($63 million). The LOS and in-hospital mortality rates were highest for intentional/self-inflicted FRIs, of which 1 in 3 patients died before discharge, and for FRIs in which a head wound occurred. Except for the youngest age group,the mortality rate increased with increasing age (from 6.9%among patients 14–17 years of age to 30% in patients ≥65 years of age).

Discussion

In the current study we investigated the 14-year frequency,prevalence, trends, and healthcare costs associated with inpatient hospitalizations for various types of FRIs in the US. One of our key findings was that despite annual fluctuation, the consistent declining trends in FRIs observed in the 1990s that happened to accompany firearms regulations legislation [16,17] did not continue in the 2000s. In fact, we did not observe any significant changes in the rate of inpatient hospitalization for any FRI subtype (assault, accidental, or intentional/self-inflicted) among most socioeconomic subgroups, except an approximate 2% annual decline within the 18–24 year age group and patients with private insurance, and a 4% annual decline in rural areas. A recent 2000–2010 study examining hospitalizations from the National Hospital Discharge Survey[18] also reported non-significant changes in the rate of hospitalizations among FRIs because of assault or accident; however, the authors did report a small reduction in the rate of self-inflicted injuries. Recently, Agarwal [19] observed that the subtle annual variations in hospitalizations for FRI mirrored changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, suggesting that stock market volatility may reflect broader economic insecurities that trigger violence and an increase in FRIs.

Table 3. Hospital length of stay, costs of inpatient care, and in-hospital mortality associated with firearm-related injuries in the United States by injury, patient, and hospital-level characteristics, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1998–2011.

Table 3. (continued)

The burden of firearm-related violence continues to disproportionately affect the young, poor, and minority males in urban settings. Sixty percent of all hospitalizations for FRIs were because of assaults; however, that percentage increased to over 70% for NH blacks and Hispanics overall,and was well above 80% for NH black and Hispanic males under 25 years of age in the lowest quartile of household incomes. Although the prevalence estimates by race/ethnicity must be interpreted with caution because of reporting in the NIS (25% of discharges have missing race/ethnicity),these gender, race/ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in fatal and non-fatal assaults with a firearm have been echoed consistently in government reports and research studies[2, 6, 19–23]. Conversely, the proportion of FRIs that were accidental or the result of an attempted suicide were more common among NH whites and patients in higher socioeconomic strata, and the rate of self-inflicted injuries increased substantially with increasing age, constituting over 40% of all hospitalizations for FRIs among patients 65 years of age or older.

The short-term outcomes associated with FRIs were similar to the short-term outcomes reported in other studies [18,19]. The mean LOS was 7 days, with a slight increase over time, and nearly 5% of patients were hospitalized a month or longer. Even for FRIs that were not immediately fatal, hospitalized patients still experienced over an 8% chance of death before discharge, a mortality rate that did not change signifi-cantly over time. As expected, self-inflicted and head injuries had the highest risk of death. The economic cost of FRIs is substantial; specifically, FRIs cost hospitals over $679 million annually on inpatient care for the index FRI hospitalization alone. Over the entire study period, the cost of FRIs equates to over $9 billion, an amount which does not include direct medical costs for physicians, indirect costs caused by lost productivity, the costs borne by families and society as a whole,or the costs for victims of FRIs who are never hospitalized.Furthermore, because the NIS does not link hospitalizations longitudinally, our estimates are extremely conservative not only for costs, but also for the overall morbidity and mortality attributable to FRIs [3–5].

Despite the strength of using of a large, nationally-representative dataset compiled and used frequently for health services research, the findings from the current and other studies on FRIs that leverage HCUP data must be interpreted within the context of the following limitations. First,despite obvious visual cues for diagnosing a FRI, the NIS relies exclusively on ICD-9-CM codes for identifying medical conditions and procedures. These codes have suboptimal sensitivity and accuracy because of errors both in translation of information from the medical record into an appropriate code and in entry of codes into the hospital information management system. Second, the NIS databases fail to capture FRIs that are immediately lethal, minor FRIs that are treated in physician’s of fices, walk-in clinics, and emergency departments without the need for hospitalization, and victims of FRIs who do not seek medical care, which may collectively comprise more than 80% of all FRIs. Therefore, the national frequency, prevalence, and trends we report reflect a particular subset of serious FRIs that result in inpatient hospitalization. Third, although we controlled for mental illness and substance abuse, we did not analyze the independent effects of these conditions on hospitalizations for FRIs. Our denominator consisted of other inpatient hospitalizations and not a population estimate, and considering the frequency of hospitalizations for people with clinically-diagnosed addictions and mental illnesses, we reasoned that comparing the relative odds of FRIs in this particular subgroup would misrepresent the desired odds of being involved in a FRI. Lastly, the NIS lacks circumstantial information regarding the victim and perpetrator, the location of the injury, and the specific firearm(s) used, particularly for accidental or assault-driven FRIs. Despite these limitations in addressing the entire scope of the problem, our analyses highlight the enormous financial cost of FRIs in the US. There are complex socio-historical, cultural, and political processes that underlie FRIs and which permeate individual, family, and community-level systems in the US [24, 25]. Although trends in FRIs remain stable over the period covered by this study, the burden of firearm-related violence continues to be disproportionately borne by young, poor, and minority males in urban settings.Comprehensive public health and legal measures to curtail FRIs should incorporate targeted measures directed to this demographic group.

conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-pro fit sectors.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2013 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2015. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2013, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. [January 12, 2015]. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html.

2. Planty M, Truman JL. Special Report: Firearm Violence,1993-2011. 2013, U.S. Department of Justice, Of fice of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington, DC.

3. Lee J, Quraishi SA, Bhatnagar S, Zafonte RD, Masiakos PT. The economic cost of firearm-related injuries in the United States from 2006 to 2010. Surgery 2014;155(5):894–8.

4. Martin MJ, Hunt TK, Hulley SB. The cost of hospitalization for firearm injuries. J Am Med Assoc 1988;260(20):3048–50.

5. Max W, Rice DP. Shooting in the dark: estimating the cost of firearm injuries. Health Aff (Millwood) 1993;12(4):171–85.

6 Cuellar AE, Stranges E, Stocks C. Hospital Visits in the U.S. for Firearm-Related Injuries, 2009: Statistical Brief #136, in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs.2006: Rockville (MD).

7. Health Care Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2011. Rockville,MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

8. Finkler SA. The distinction between cost and charges. Ann Intern Med 1982;96(1):102–9.

9. Salemi JL, Comins MM, Chandler K, Mogos MF, Salihu HM.A practical approach for calculating reliable cost estimates from observational data: application to cost analyses in maternal and child health. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013;11(4):343–57.

10. Song X, Friedman B. Calculate Cost Adjustment Factors by APR-DRG and CCS Using Selected States with Detailed Charges. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2008-04. Online October 8, 2008. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

11. Sun Y, Friedman B. Tools for more accurate inpatient cost estimates with HCUP databases, 2009. Errata added October 25,2012. 2012. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2011-04. ONLINE October 29, 2012. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

12. National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.1.1.3 Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch and Data Modeling Branch, Surveillance Research Program[January 4, 2015]. Available from: http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/.

13. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19(3):335–51.

14. Houchens RL, Elixhauser A. Using the HCUP nationwide inpatient sample to estimate trends (updated for 1988–2004). HCUP methods series Report # 2006-05 online. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2006_05_NISTrendsReport_1988-2004.pdf.

15. United States Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics,Consumer Price Index: all urban consumers–(CPI-U). 2012.

16. Ludwig J, Cook PJ. Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady handgun violence prevention act.J Am Med Assoc 2000;284(5):585–91.

17. Safavi A, Rhee P, Pandit V, Kulvatunyou N, Tang A, Aziz H, et al.Children are safer in states with strict firearm laws: a National Inpatient Sample study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76(1):146–50;discussion 150–1.

18. Kalesan B, French C, Fagan JA, Fowler DL, Galea S. Firearmrelated hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality in the United States, 2000-2010. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179(3):303–12.

19. Agarwal S. Trends and burden of firearm-related hospitalizations in the United States Across 2001-2011. Am J Med 2015;128(5):484–92.

20. Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel D, Parks S, Patel N. Surveillance for violent deaths – National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 2012;61(6):1–43.

21. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief 2014;(178):1–8.

22. Leventhal JM, Gaither JR, Sege R. Hospitalizations due to firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2014;133(2):219–25.

23. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010.Natl Vital Stat Rep 2013;61(4):1–117.

24. Altheimer I, Boswell M. Reassessing the association between gun availability and homicide at the cross-national level. Am J Crim Just 2012;37:682–704.

25. Makarios MD, Pratt TC. The effectiveness of policies and programs that attempt to reduce firearm violence. Crime Delinquency 2012;58(2):222–44.

1. Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston,Texas, USA

2. Department of Occupational Health, Kaiser Permanente,Lancaster, California, USA

3. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida,USA

4. Department of Community Health Systems, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

5. Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health, Vanderbilt University,Nashville, Tennessee, USA

Jason L. Salemi, PhD, MPH

Department of Family and Community Medicine

3701 Kirby Drive, Suite 600,Houston, TX 77098, USA

Tel.: +713-798-4698

E-mail: Jason.Salemi@bcm.edu

25 March 2015;

15 April 2015

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年2期

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年2期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Evaluation of obstetrics procedure competency of family medicine residents

- Student self-assessment of strengths and needed improvements during a family medicine clerkship

- Depression and race affect hospitalization costs of heart failure patients

- Rural congestive heart failure mortality among US elderly,1999–2013: Identifying counties with promising outcomes and opportunities for implementation research

- Exploring point-of-care transformation in diabetic care: A quality improvement approach

- Adult immunization improvement in an underserved family medicine practice