Menopause and the risk of metabolic syndrome among middle-aged Chinese women

Mark A. Strand, Andrea Huseth-Zosel, Meizi He, Judith Perry

1. Pharmacy Practice, Master of Public Health Program, North Dakota State University, P.O.Box 6050, Fargo, ND, 58108

2. Master of Public Health Program, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND

3. Kinesiology, Health, and Nutrition Department, University of Texas at San Antonio,San Antonio, TX

4. Medical Department, Shanxi Evergreen Service, Taiyuan,China

Menopause and the risk of metabolic syndrome among middle-aged Chinese women

Mark A. Strand1, Andrea Huseth-Zosel2, Meizi He3, Judith Perry4

1. Pharmacy Practice, Master of Public Health Program, North Dakota State University, P.O.Box 6050, Fargo, ND, 58108

2. Master of Public Health Program, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND

3. Kinesiology, Health, and Nutrition Department, University of Texas at San Antonio,San Antonio, TX

4. Medical Department, Shanxi Evergreen Service, Taiyuan,China

Objective:This study explored the relationship between menopause and metabolic syndrome(MetS), stroke, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and hypertension.Study design:This cross-sectional study surveyed 440 women in Yuci, China in 2012.Main outcome measures:MetS, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, and behavioral and demographic variables.Results:The prevalence of MetS in this study was 40.28% to 49.66% (p=0.065) among preand post-menopausal women, respectively, after adjusting for age.Conclusions:The prevalence of diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was higher among post- than pre-menopausal women. Health screenings for women in China should consider the increased risk for metabolic disorders during the postmenopausal stage of life.

Post-reproductive health; public health; chronic disease; menopause

Introduction

Lifestyle characteristics, such as diet and levels of physical activity, are changing rapidly in China [1], thus significantly altering the metabolic profile of the population [2]. Changes in lifestyle characteristics contribute to increased rates of disease, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [3, 4].

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a group of inter-related risk factors, which include abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia,insulin resistance, impaired glucose regulation, and hypertension (HTN). MetS affects 20%–30% of the population in developed countries, [5] and is associated with a significant risk of CVD and type 2 diabetes,especially in men >45 years of age and women>55 years of age [6]. With development of an industrialized and urbanized society, chronic diseases now account for 80% of all deaths in China [7], having increased significantly in recent years [4].

The rate of chronic diseases, including CVD, among men exceeds that of women in mid-life [8]. Thus, CVD has often been assumed to be a disease of men, despite the fact that the mortality rate due to CVD in women increases similar to men across the lifespan [9, 10]. The rate of diabetes is higher among men than women until 60 years of age,when the rate exceeds men [11]. Gender-based differences in the timing and development of chronic diseases, particularly in the menopausal transition for women, need to be investigated further. There is a risk that lack of research into menopause and associated health risks puts women at risk for a compromised quality of life and increased disease burden [12].

The aim of the research reported in this paper was to determine the association between MetS risk factors and correlated diseases among women before and after the menopause. Our specific aims were as follows:

1. Determine the prevalence of MetS among pre- and postmenopausal women 48–56 years of age;

2. Determine the prevalence of diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in pre- and post-menopausal women 48–56 years of age; and

3. Consider the metabolic risks for women posed by the menopause.

Methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was conducted to compare the rates of MetS in 3 age cohorts (born in 1956, 1960–1961, and 1964 in Yuci District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province, China).These age cohorts were chosen as part of a larger study comparing individuals born in 1960–1961 with individuals born before and after the famine (1954 and 1956). Data was collected in the latter one-half of 2008 and 2012, respectively,in Yuci District (population = 300,000). No menopausal data was collected in 2008, thus the present paper reports on the cross-sectional data collected in 2012. Yuci is a satellite city to the provincial capital of Taiyuan, and while accommodating many rural migrants into the city in recent years, immigration from outside the province is limited. At the time of the survey, participants were required to have been born in Jinzhong City, not currently under treatment for tuberculosis or cancer, not currently taking corticosteroids, and not currently pregnant.

Two-thirds of the participants were recruited through 16 of 19 community health centers (CHCs) in Yuci District using the Health Record Database of each CHC, which contains the names of all enrolled individuals in the capitation area. Participants were recruited by telephone invitation, posters in the community and word of mouth. The intensity of recruitment varied by center, as did the participation rate, with up to 80% participation at one center,but an average response rate of approximately 10%. Centers with a high population of residents born outside Jinzhong were not included in the data collection. The remaining one-third of the participants was recruited through the Jinzhong Hospital Health Examination Center. Individuals examined at this facility were primarily healthy individuals whose employer arranges an annual physical examination. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before data collection.

A total of 806 people completed the cohort study in 2008,of which 13 were excluded due to failure to meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 659 people completed the follow-up study in 2012, with a loss-to-follow up rate of 16.9%. Two hundred and nineteen males were excluded, leaving 440 female participants for the data analysis. This paper will only analyze the 2012 data.

Data collection

Laboratory:Overnight fasting blood samples were drawn by venipuncture to measure serum glucose, total cholesterol,triglycerides, high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol. All samples were analyzed within 3 h at the Jinzhong People's Hospital Laboratory on a Roche Diagnostics Modular P800 Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using the reagents imported from Roche Diagnostics.

Anthropometric measurements:Weight, height, and waist circumference were measured by trained staff according to a standard protocol. Participants were weighed (without shoes), but with light summer clothing, and when the season changed, 1–2 kg was deducted to adjust for heavier fall and winter clothing. Standing height was measured in meters(without shoes) with a stadiometer attached to a scale (Su Hong Medical Equipment Company, Limited, Jiangsu, China).Measurements were taken to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Waist circumference was measured with the participant standing erect using a standard tape measure. Measurement was taken at the umbilicus, with the tape being horizontal and passing just above the iliac crest.

Blood pressure measurement:At least two blood pressure measurements were obtained 1 min apart by trained nurses and physicians. The protocol was adapted from the American Heart Association recommendations [13]. The blood pressure was the last procedure completed to insure that the participants had 30 min of rest after any exercise or smoking. A standard mercury sphygmomanometer was used, and calibrated at the Jinzhong People's Hospital Medical Equipment Department twice during the study period. For this Chinese population, the standard cuff was suitable for all participants. All measurements were averaged.

Survey

A 47-item survey was designed by 2 Chinese and 2 American MetS and chronic disease experts. The survey was pilot-tested to ensure face validity. The survey was administered by trained research staff to all participants, assessing demographic data,personal and family medical histories of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and heart disease, exercise (moderate and vigorous activity done for >10 min at a time, including activities associated with commuting, working, and leisure), smoking(never smoked, quit >1 year, and smoked at least 1 cigarette a day), alcohol intake volume and frequency (never, occasional,quit, and >twice a week), menopausal status (post-menopause defined as 12 months without menses), and self-reported health score (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, and 4=excellent).

Definition of MetS

The primary outcome measure was rate of MetS, as defined by the revised NCEP ATP III criteria [14], using the Asian criteria for waist circumference [15].

MetS is the presence of >3 of the following risk determinants:

1) increased waist circumference (≥90 cm for men, ≥80 cm for women [Asian standards]);

2) elevated triglycerides (≥1.7 mmol/L [150 mg/dL]) or treatment for this lipid abnormality;

3) low HDL-cholesterol (<1.03 mmol/L [<40 mg/dL] in men and <1.29 mmol/L [50 mg/dL] in women), or treatment for this lipid abnormality;

4) hypertension (≥130/≥85 mm Hg) or treatment for hypertension; and

5) impaired fasting glucose (≥5.6 mmol/L [100 mg/dL]) or treatment for elevated blood glucose.

Data analysis

Responses from 440 female participants for 2012 were analyzed. Data on sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age,education, and income), lifestyle (exercise, alcohol drinking, and smoking), menopausal status, and health status were described using percentages, means, standard deviations, and compared using ANOVA or chi-square tests. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between menopausal status and the above variables. Model fitting likelihood ratio and chi-square test (significance) values were 13.595 (0.009) and 93.801 (0.000), as shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. A 0.05 significance level was used for all tests.All analyses were performed using the statistical software(SPSS 20.0 for Windows).

Results

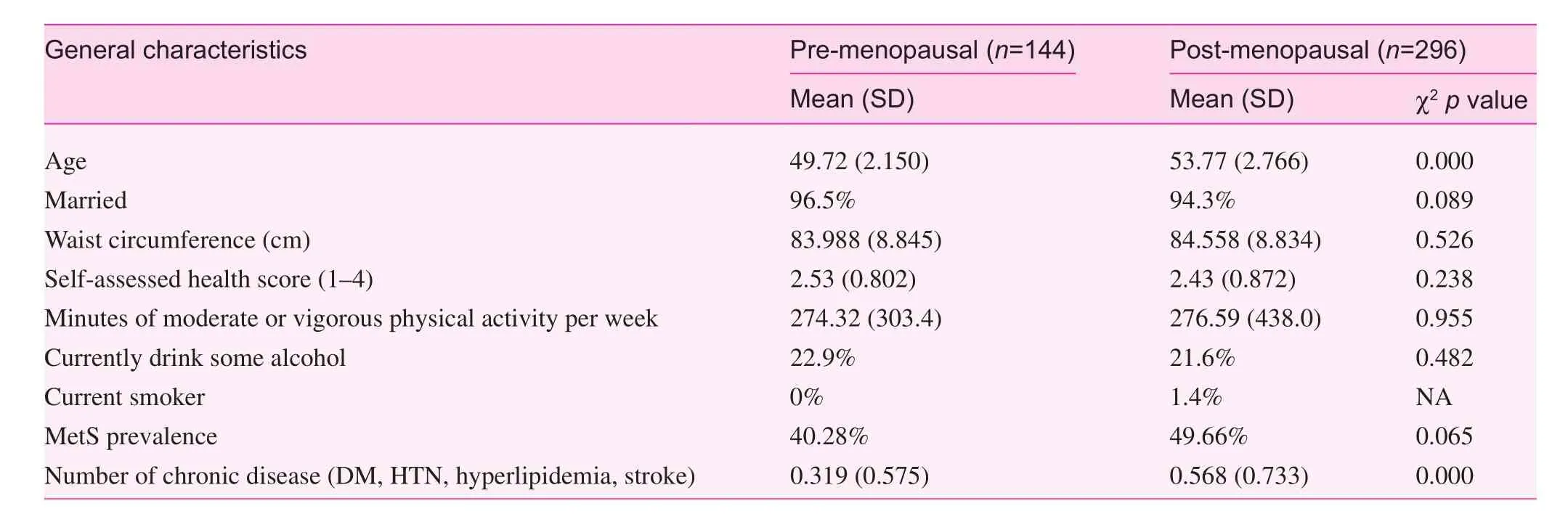

The participants in this study had an average age of 48.72 and 53.77 years among pre- and post-menopausal women,respectively (Table 1). The median age of menopause was 50 years and the average duration of menopausal symptoms was 4.70±3.6 years. Post-menopausal women had a higher prevalence of MetS, and a higher number of chronic diseases than pre-menopausal women (Table 1). No difference in selfassessed health was observed between the two groups, with a mean self-assessed score for both groups representing health between fair and good. Pre- and post-menopausal women had a mean exercise time of 274.32 and 276.59 min per week,respectively, both of which exceeded the target of 150 min per week.

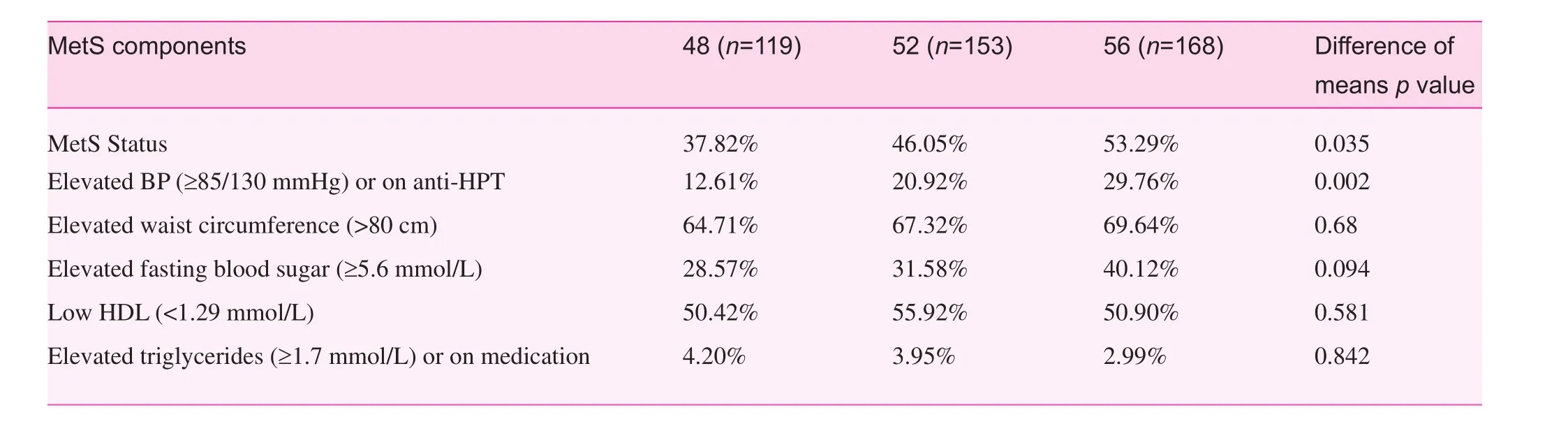

The prevalence of MetS was 37.82%, 46.05%, and 53.29%,for women 48, 52, and 56 years of age, respectively (p=0.035).Table 2 shows the prevalence of the five components that make up the MetS for each of the 3 age cohorts (48, 52, and 56 year).Increased waist circumference and a low HDL-cholesterol level were the two MetS components that contributed most significantly to the presence of MetS in each age cohort.Elevated blood pressure and fasting blood glucose were two components that showed an increase with each increase in age increment.

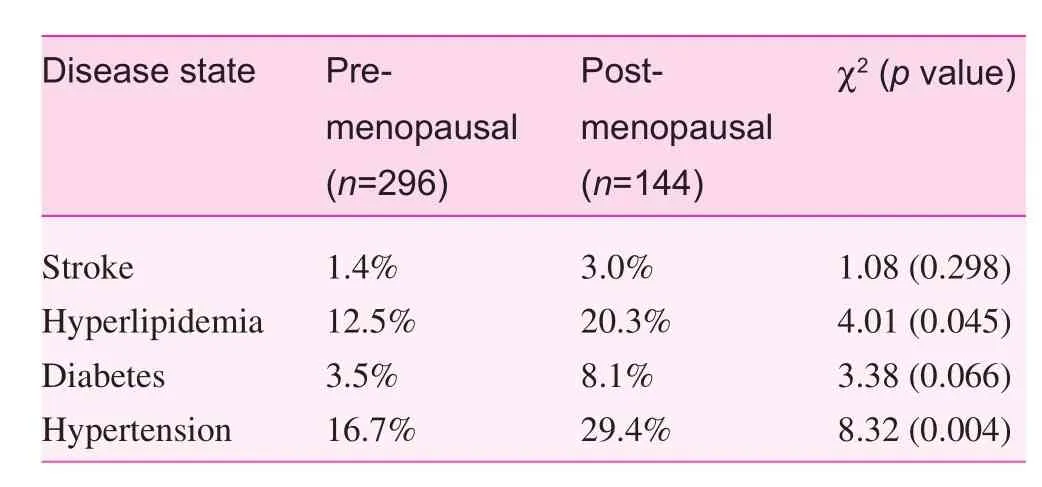

Post-menopausal women had significantly higher rates of hyperlipidemia and hypertension than pre-menopausal women(Table 3). The prevalence of stroke and diabetes was also higher for post-menopausal than pre-menopausal women, but the difference was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level.The average number of chronic diseases (total of 4) was 0.319 and 0.568 for pre- and post-menopausal women, respectively,even after adjusting for age (p=0.000).

Table 1. General characteristics of the sample (n=440)

Table 2. Prevalence of MetS components with age

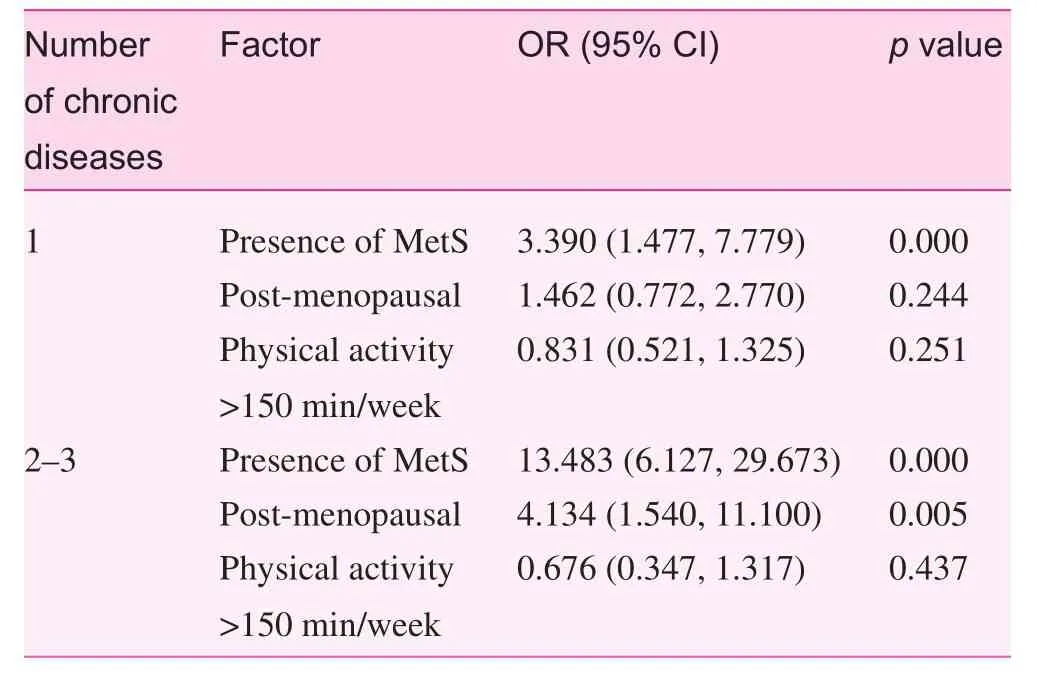

Regression analysis showed that the presence of MetS was significantly associated with the presence of chronic diseases in a gradient fashion (Table 4). Being post-menopausal was significant for the presence of two or three chronic diseases, but not for the presence of only one chronic disease. Physical activity was protective against the presence of chronic diseases, with an OR of 0.831 and 0.676 for 1 and 2–3 chronic diseases, respectively, but neither were statistically significant.

Table 3. Prevalence of self-reported disease states of pre- and post-menopausal women

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of MetS was higher among post-menopausal women, regardless of age. MetS is a known predictor of diabetes and CVD, thus the results reported heresuggest the possibility of elevated risk for diabetes and CVD after menopause. Although it has been erroneously viewed as a disease primarily of men, CVD is the primary cause of death in women in Western countries [16]. Menopause has been shown to predict MetS in non-Western countries [17, 18],but the results have been inconsistent [19]. It is known that women develop chronic disease approximately 10 years later than men, with a marked increase through the menopausal years [20–22].

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression analysis for correlates of chronic disease

A hallmark of the menopausal transition is the dramatic reduction in estradiol levels. With this reduction, there is a progressive shift toward androgen dominance in the hormonal milieu [23]. Little is known about how this hormonal shift influences CVD risk [24], for the replacement of estrogen does not protect against CVD [23].

The proportion of women in this study in whom blood pressure and fasting blood glucose exceeded the criteria used in determining MetS increased with each age increment. A higher risk of elevated blood pressure may reflect the loss of circulating estrogen associated with menopause. It is possible that post-menopausal women exhibit poorer control of blood pressure than pre-menopausal women, but unlikely. The relationship between menopause and blood pressure is still unclear worldwide [25].

The women in this study already had a high rate of increased waist circumference at all ages, which was the component most significantly contributing to the presence of MetS in this cohort of women. Limiting weight gain during menopause is difficult, but extremely important because abdominal fat is a major contributor to insulin resistance. Abdominal obesity,particularly visceral adiposity, contributes to insulin resistance and eventual diabetes [26]. The prevalence of elevated glucose in women increased steadily from 48 to 56 years of age, while the prevalence of elevated blood glucose for men was constant across the 3 age cohorts.

The results from other studies are inconsistent with respect to weight gain among women due to aging or menopause.Women tend to gain weight and accumulate visceral adipose tissue during the transition through menopause [27–29].Estrogen deficiency has been shown to partially contribute to excessive visceral fat accumulation, insulin resistance,and increasing risks of cardiovascular diseases among postmenopausal women [27, 28]. It has been suggested that estrogen acts on android fat to enhance lipolysis and on gynoid fat to suppress lipolysis, but enhance lipoprotein lipase activity. Thus, estrogen promotes mobilization of android fat and deposition of gynoid fat [30]. Estrogen has favorable effects on the lipid profile and insulin sensitivity [31–33], thus offering a protective effect against metabolic disorders.

The prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia,and stroke is higher among post-menopausal women than premenopausal women; however, being post-menopausal was only associated with the presence of chronic diseases in a statistically significant manner among women with two or three chronic diseases. This suggests the possibility that the end of menses contributes to the increased presence of chronic diseases among a distinct segment of at-risk women, but not among all women.Therefore, particular attention should be paid to early identifi-cation of at-risk women by the utilization of a MetS screening tool at the time when the metabolic profile of women begins to change remarkably (approximately 44 years of age [34, 35]).

Although mortality due to CVD among women at 45 years of age is one-half that of men, the mortality rate increases 4-fold in women between age 45 and 55 years of age and is higher among menopausal women than men of comparable age [34, 35]. Among men and women, Ford et al. [21] reported MetS rates to increase with age in a linear fashion before leveling out at 60 years of age. In agreement with these findings and studies in other Asian populations [36], our study showed that prevalence of MetS increased in men in their 40s and decline after 50 years of age, and in women the rates sharply increase between 48 and 52 years of age [3]. By 56 years of age, the prevalence of MetS in women approximate those of men of the same age due to higher rates of extreme central adiposity and elevated blood pressure.

This group of Chinese women faced rapidly worsening health status, with an increasing burden created by menopause and the cost of managing the symptoms. This epidemiologic phenomenon will occur in a population of women with a rather unique history. To appreciate the impact, it is important to better understand this population of women.

Women are universally healthier than men in their 40s due to better lifestyles and the protective effects of estrogen. One could assume that chronic diseases are more of a concern for men than women. Additionally, women tend to delay seeking health care longer than men, in part because of the sense that they are the family caregiver and do not have time to take sick leave from the family [37, 38]. Gender roles and healthseeking behavior are controversial [39], but there is consistent evidence globally for a lack of attention paid to women and CVD. While there has been increased attention to the need for women to receive classic gynecologic preventive services, such as mammograms and cervical cancer screenings, women need to receive increased screenings for metabolic disorders in the menopausal period. Women shown to be pre-diabetic or women with elevated cholesterol or blood pressure should be treated aggressively to prevent CVD. Although hormone replacement therapy gives protection against menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis, hormone replacement therapy has been shown to increase rates of breast cancer and myocardial infarction, so hormone replacement therapy is recommended for short-term use only. Culturally- and gender-sensitive medical care for menopausal women is needed in China, and around the world.

Limitations

As a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to determine with certainty the temporal relationship between menopause and the onset of the reported diseases. This study is part of an 8-year longitudinal study, however, so these questions will be elucidated with time.

This study was limited by low response rates in each age cohort, particularly among the men, and the localized nature of the surveyed population. The survey instrument was not validated, so misclassification bias was a possibility. The generalizability of this study was limited to middle-aged, lower middle income urban women in Shanxi Province, China.Selection bias was unavoidable as the study participants chose to participate in the study and may not be representative of the community at large, although whether or not the general population is healthier than this group is unknown. Recall bias was also present as questions required recall of habits in the previous month or longer. Only 16.9% of the participants were lost to follow-up from the first phase of this longitudinal study,but the self-perceived health scores of these individuals was higher, thus compromising the generalizability of the results to all populations.

Future research

Current preventive health guidelines should take into consideration menopausal status. While there is the risk of medicalizing menopause, or over-treating menopause, chronic disease screening for women needs to be attentive to the potential increase in the risk for metabolic disorders in the postmenopausal stage of life. Another question to be further investigated is the role of hormone replacement therapy to improve the metabolic profile, such as lower rates of weight gain,hypertension, and insulin sensitivity. As a longitudinal study,the eventual completion of this research will allow elucidation of the development of MetS by age and gender. Finally, early age at menarche is associated with all-cause mortality [40], so it would be valuable to know whether or not early menopause also predicts early mortality.

Conclusions

The prevalence of MetS and associated chronic diseases,including diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, was higher among post- than pre-menopausal women.Menopause should be considered a critical time to screen women for the presence of risk factors known to predict cardiovascular disease. In particular, the MetS screen is an easy and highly sensitive tool to be used. Health screenings for women in China should consider the increased risk of metabolic disorders in the postmenopausal stage of life, and provide cultural-sensitive services to this at-risk population of women.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at Evergreen and the Jinzhong First People's Hospital whose hard work made this study and manuscript possible. This research was done under the authority of the Shanxi and Yuci Public Health Bureaus. The research proposal was approved by the Research Ethics Board (REB)of the University of Western Ontario and the Jinzhong City Science Commission and Yuci District Public Health Bureau(Western Ontario review number: 15309E).

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Partial funding for this research was provided by the Cedar Fund (Hong Kong, SAR).

1. Visscher TLS. Public health crisis in China is about to accelerate the public health crisis in our world's population. Eur Heart J 2012;33:157–9.

2. Muntner P, Gu D, Wildman RP, Chen J. Prevalence of physical activity among Chinese adults: results from the international collaborative study of cardiovascular disease in Asia. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1631–6.

3. Strand MA, Perry J, Wang P, Liu S, Lynn H. Risk factors for metabolic syndrome in a cohort study in a north China urban middle-aged population. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27(2):NP255–NP265.

4. Yang Z-J, Liu J, Ge J-P, Chen L, Zhao Z-G, Yang W-Y. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor in the Chinese population: the 2007–2008 China national diabetes and metabolic disorders study. Eur Heart J 2012;33:213–20.

5. AlSaraj F, McDermott J, Cawood T, McAteer S, Ali M,Tormey W, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with diabetes mellitus. Irish J Med Sci 2009;178:309–13.

6. Lorenzo C, Williams K, Hunt K, Haffner S. The national cholesterol education program-adult treatment panel iii, international diabetes federation, and world health organization definitions of metabolic syndrome as predictors of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:8–13.

7. Wang L, Kong L, Wu F, Bai Y, Burton R. Preventing chronic diseases in China. Lancet 2005;366:1821–4.

8. Preis SR, Hwang S-J, Coady S, Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB,Savage PJ, et al. Trends in all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among women and men with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study, 1950–2005. Circulation 2009;119:1728–35.

9. Writing Group M, Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM,Carnethon M, Dai S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics– 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association.Circulation 2010;121:e46–215.

10. Gu D, He J, Duan X, Reynolds K, Wu X, Chen J, et al. Body weight and mortality among men and women in hina. J Am Med Assoc 2006;295:776–83.

11. Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1090–101.

12. Duffy O, Iversen L, Hannaford P. The menopause "It's somewhere between a taboo and a joke." A focus group study. Climacteric 2011;14:497–50.

13. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN,et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the american heart association council on high blood pressure research.Circulation 2005;111:697–716.

14. Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome scientific statement by the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:2243–4.

15. Heng D, Ma S, Lee J, Tai B, Mak K, Hughes K, et al. Modification of the NCEP ATPIII definitions of the metabolic syndrome for use in Asians identifies individuals at risk for ischemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis 2006;186:367–73.

16. Mosca L, Mochari-Greenberger H, Dolor RJ, Newby LK,Robb KJ. Twelve-year follow-up of American women's awareness of cardiovascular disease risk and barriers to heart health.Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2010;3:120–7.

17. Estiaghi R, Esteghamati A, Nakhjavani M. Menopause is an independent predictor of metabolic syndrome in Iranian women.Maturitas 2010;65:262–6.

18. Marroquin O, Kip K, Kelley D, Johnson B, Saw L, Bairey Merz C, et al. Metabolic syndrome modifies the cardiovascu-lar risk associated with angiographic coronary artery disease in women: A report from the women's ischemia syndrome evaluation. Circulation 2004;109:714–21.

19. Carr MC. The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. The J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2003;88:2404–11.

20. Expert Panel on Detection E, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). J Am Med Assoc 2001;285:2486–97.

21. Ford E, Giles W, Dietz W. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Am Med Assoc 2002;287:356–9.

22. Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G and the American Heart Association Statistics Subcommittee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee.Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2007 update: A report from the american heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation 2007;115:e69–17.

23. Janssen I PLHCSLBS-TK. Menopause and the metabolic syndrome: The study of women's health across the nation. Archiv Int Med 2008;168:1568–75.

24. Guthrie J, Taffe J, Lehert P, Burger H, Dennerstein L. Association between hormonal changes at menopause and the risk of a coronary event: a longitudinal study. Menopause 2004;11:315–22.

25. Coylewright M, Reckelhoff JF, Ouyang P. Menopause and hypertension: an age-old debate. Hypertension 2008;51:952–9.

26. Tchernof A, Després J-P. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev 2013;93:359–404.

27. Sites CK, Toth MJ, Cushman M, L'Hommedieu GD, Tchernof A,Tracy RP, et al. Menopause-related differences in inflammation markers and their relationship to body fat distribution and insulin-stimulated glucose disposal. FertilSteril 2002;77:128–35.

28. Tchernof A, Calles-Escandon J, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Menopause, central body fatness, and insulin resistance: effects of hormone-replacement therapy. CoronArtery Dis 1998;9:503–11.

29. Tchernof A, Poehlman ET, Despres JP. Body fat distribution, the menopause transition, and hormone replacement therapy. Diabetes Metab 2000;26:12–20.

30. Orgaard A, Jensen L. The effects of soy isoflavones on obesity.Exp Biol Med 2008;233:1066–80.

31. Barrett-Connor E. Hormones and heart disease in women: the timing hypothesis. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:506–10.

32. Barrett R, Kuzawa CW, McDade T, Armelagos GJ. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases: the third epidemiologic transition. Annu Rev Anthropol 1998;27:247–71.

33. Bell R, Davison S, Papalia M, McKenzie D, Davis S. Endogenous androgen levels and cardiovascular risk profile in women across the adult life span. Menopause 2007;14:630–8.

34. Collaboration PS. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. The Lancet 2002;360:1903–13.

35. Kannel W, Hjortland M, McNamara P, Gordon T. Menopause and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med 1976;85:447–52.

36. Ko G, Tang J. Metabolic syndrome in the Hong Kong community: the united christian nethersole community health service primary healthcare programme 2001–2002. Singapore Med J 2007;48:1111–16.

37. O'Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G. It's caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate: men's accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:503–16.

38. Courtenay W. Engendering health: A social constructionist examination of men's health beliefs and behaviors. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 2000;4–15.

39. Galdas PM, Johnson JL, Percy ME, Ratner PA. Help seeking for cardiac symptoms: beyond the masculine–feminine binary. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:18–24.

40. Tamakoshi K, Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi A. Early age at menarche associated with increased all-cause mortality. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26:771–8.

Mark A Strand Pharmacy Practice, Master of Public Health Program, North Dakota State University, P.O.Box 6050, Fargo, ND, 58108

E-mail: Mark.Strand@ndsu.edu Tel.: +701-231-7497

14 November 2014;

Accepted 24 December 2014

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年1期

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年1期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Effectiveness of an employment-based smoking cessation assistance program in China

- Team-based stepped care in integrated delivery settings

- The Accountable Care Organization results: Population health management and quality improvement programs associated with increased quality of care and decreased utilization and cost of care

- "Three essential elements" of the primary health care system:A comparison between California in the US and Guangdong in China

- Availability and social determinants of community health management service for patients with chronic diseases:An empirical analysis on elderly hypertensive and diabetic patients in an eastern metropolis of China

- Evaluating the process of mental health and primary care integration:The Vermont Integration Profile