Clay in the Potter’s Hands

By Xiao Qiang

Clay in the Potter’s Hands

By Xiao Qiang

Wang Lingtao refers to a large amount of historical documents to find inspiration for his work.

Hidden in the mountainous Caishi Town in the eastern suburbs of Jinan, capital of eastern China’s Shandong Province, Wang Lingtao’s courtyard is accentuated by an awe-inspiring array of clay sculptures he recently finished working on. These sculptures include Confucius (a great philosopher and educator of ancient China) standing in a courteous and polite manner at the front, followed by a

In Wang’s hands, a handful of clay can be easily turned into any one of thousands of figures in various shapes and postures. Displayed at his studio are nearly 100 clay figurines, which have become an integral part of his life.

formation of his 72 disciples, altogether creating an epic scene. Varying in posture, either holding bamboo slips in their hands or bowing with their hands clasped in front of their chest, sculptures of the 72 disciples seem to almost come to life thanks to their level of detail, especially in their beards, eyebrows and the folds of their clothes.

After graduating from a cooking school in Jinan, Wang began working at a five-star hotel, where he had engaged in vegetable carving and plate decoration for 20 years. Each time he saw his vegetable carvings discarded right after a banquet finished, Wang felt sad. Gradually, a dream began to take shape in his mind — shifing to clay sculpture work to prevent his work from being disposed of. Last year, in pursuit of this dream, Wang quit his hotel job, rented a farmer’s courtyard in a mountain village and began his “Confucius” sculpture production.

In Wang’s hands, a handful of clay can be easily turned into any one of thousands of figures in various shapes and postures. Displayed at his studio are nearly 100 clay figurines, which have become an integral part of his life.

“As a native of Shandong [where Confucius’ hometown is located], I began to be influenced by Confucian philosophy when I was a child, and

have always regarded the Sage as the beacon of my soul,” Wang explained.“That’s why I devoted my first clay sculpture to my idol.”

Any items discovered to be flawed must be repaired and dusted before being placed into the kiln.

Placing the items on the firing tray in a stable and orderly manner requires meticulous work.

Given the fact that existing ancient books have limited descriptions of Confucius’ disciples, and do not include pictures or drawings that can help restore their original images, Wang referred to a large amount of historical documents and relevant material including portraits of ancient people, attempting to find inspirations for creation.

The kiln needs to be heated up gradually to function properly.

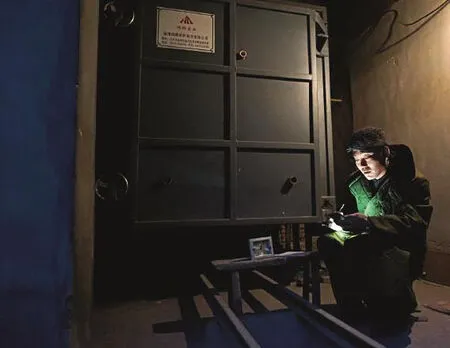

During the firing process, Wang often watches the kiln for 10 straight hours.

Deep into the night, Wang is still observing the kiln.

“Consulting pictures of ancient people was far from enough,” Wang said. “Graphic images are actually different from sculptures, and only when you gain an understanding of the life of the figure can you come to realize in which posture his personality could be best represented.”

Finally, using the work of renowned painter Dai Dunbang as a prototype, Wang created a massive set of sculptures of Confucius and his disciples.

Clay sculpture production requires a dozen steps including clay collecting, molding, drying, polishing and coloring. At least 80 percent of the process is done manually, and only the nooks that cannot be reached by fingers need the help of a minzi, a kind of willow-leaf-shaped blade, about 10 centimeters long and 1 centimeter wide. Minzi are often made of bamboo, rosewood or sandlewood. Such tools are available for purchase, but Wang prefers to crae them himself, since “homemade tools are easier to use”.

Clay sculptures are difficult to preserve. In order to address this drawback, Wang spent substantial sums of money erecting a kiln, and invited a hearing-impaired seasoned artisan to help him fire the works. Placing the items on the firing tray in a stable and orderly manner requires meticulous work and usually takes three to four hours. Any items discovered to be flawed must be repaired and dusted before being placed into the kiln.

The kiln should be heated up gradually. Throughout the two or three days of firing, Wang and his assistant took turns watching the kiln, recording the temperatures at regular intervals. The kiln’s temperature can reach 1,180 degrees Celsius, high enough to burn dark a pencil in just an instant. Despite such a tough environment, Wang often watched the kiln for more than 10 hours straight.

From chef to artist, Wang has remained dedicated to a pursuit of precision and excellence, with the spirit of craftsmanship vividly embodied in his works.

- China Report Asean的其它文章

- Fuzhou at the Forefront of Maritime Silk Road Tourism Development

- COVER STORY NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHINA AND ASEAN IN THE EYES OF JOURNALISTS

- Investment in ASEAN Requires Close Attention to Development Situation

- Marine Economy Cooperation Harbors Potential

- China-Philippines Relations Set Sail Again

- My New Home in Yangon