The Future for the Enterprise

CHANG Hong

I. Introduction

In October 2012, the Secretary-General of the International Seabed Authority(hereinafter “the Authority”) received a proposal from Nautilus Minerals Inc., a company incorporated in Canada, to enter into negotiations to form a joint venture with the Enterprise for the purpose of developing eight of the reserved area blocks in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.1See International Seabed Authority document ISBA/19/C/4.According to Article 170 and Annex IV of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter the “Convention”),2United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, United Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 1833,p. 3. [hereinafter the “Convention”]the Enterprise is established as the organ of the Authority that is to carry out activities in the Area directly, as well as the transporting, processing and marketing of minerals recovered from the Area.3The Area is defined in the Convention Article 1(1) as “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.”As required by the Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 (hereinafter the “1994 Agreement”),4At http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm, 9 January 2017.the Secretariat of the Authority shall perform the functions of the Enterprise until it begins to operate independently.5The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 1.However, only under two circumstances can the Enterprise be activated and operate independently of the Secretariat of the Authority. These are firstly, the approval of a plan of work for exploitation of an entity other than the Enterprise, or secondly, the Council’s receipt of an application for a joint-venture operation with the Enterprise.6The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 2.If joint-venture operations with the Enterprise accord with sound commercial principles, the Council shall issue a directive to provide for such independent functioning.7The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 2.In 2013, however, the Council decided that it was premature for it to make a decision to permit the Enterprise to function independently.8The International Seabed Authority, ISBA/19/C/18, para. 16, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/isba-19c-18_0.pdf, 9 January 2017.It is therefore clear that there was no political will, at that stage, to consider allowing the Enterprise to function independently. Other than that, the fact that the specific joint venture proposal in question overlapped with reserved area sites already subject to applications for exploration by developing countries also complicated the situation.9On 19 April 2013, Ocean Mineral Singapore Pte. Ltd., a company sponsored by the Government of Singapore, submitted an application for approval of a plan of work for exploration for polymetallic nodules in a reserved area. The application covers an area which is also included in the proposal offered by Nautilus Minerals Inc. for a joint venture operation with the Enterprise. At https://www.isa.org.jm/news/singapore-applies-approvalplan-work-exploration-polymetallic-nodules, 9 January 2017.

II. The Legislative History of the Enterprise

It has been stated that “from the very beginning of discussions about how to realize the benefits of the common heritage of mankind there was a fundamental divergence of views as to whether deep seabed mining would be carried out by private sector or state entities under some kind of licensing system, with access controlled by a central licensing body or agency, or through an international entity specifically established to carry out mining on behalf of the international community.”10Donald Rothwell, Alex Oude Elferink, Karen Scott and Tim Stephens eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 237.The creation of an International Seabed Enterprise was first proposed in 1971 by thirteen Latin American States in the Sea-Bed Committee.11Satya N. Nandan, Michael Lodge and Shabtai Rosenne eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. VI, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1993, p. 512.It remained controversial until 1976, when the U.S. Secretary of State proposed a“parallel system” that guaranteed developing States’ exclusive access to some mine sites through the Enterprise, while developed States and private operators freely get access to other sites.12Satya N. Nandan, Michael Lodge and Shabtai Rosenne eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. VI, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1993, p. 297.This proposal was then quickly accepted as the basis of the system for access to seabed minerals, and it was embodied in Article 153 of the Convention thereafter.13Satya N. Nandan, Michael Lodge and Shabtai Rosenne eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. VI, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1993, p. 297.The issue of the financing of the Enterprise, along with the issue of technology transfer, continued to be discussed throughout the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) and in the negotiations that lead to the 1994 Agreement.14Donald Rothwell, Alex Oude Elferink, Karen Scott and Tim Stephens eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 238.

After several years of negotiations, the Enterprise regime was finalized in Articles 153 and 170 of the Convention, Annexes III and IV. Accordingly, the Enterprise is the organ of the Authority to directly carry out all of the exploration activities for, and the exploitation of, the resources of the Area.15Satya N. Nandan, Michael Lodge and Shabtai Rosenne eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. VI, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1993, p. 523.Furthermore,the Enterprise is empowered to undertake the related activities of transporting,processing and marketing of minerals that are recovered from the Area, regardless of the form of such resources, and no matter whether or not these resources are recovered by the Enterprise itself or by any other mining entities.16Satya N. Nandan, Michael Lodge and Shabtai Rosenne eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. VI, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1993, p. 523.Most importantly, based on Article 170 of the Convention and Article 5 of Annex III, the Enterprise enjoys a series of privileges regarding gaining access to deep seabed mining technologies, and it has been the recipient of an almost “mandatory transfer of technology.”17Kenneth Rattray, Assuring Universality: Balancing the Views of the Industrialized and Developing Worlds, in Myron H. Nordquist and John Norton Moore eds., Entry Into Force of the Law of the Sea Convention, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1995, p. 60. See also Satya N.Nandan, Michael Lodge and Shabtai Rosenne eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. VI, Dordrecht: Nijhoff, 1993, p. 521.Additionally, pursuant to Article 170 of the Convention and Article 11 of Annex IV, the Enterprise can be provided with funds by the Authority and State Parties, including voluntary contributions and direct loans.

From 1990 to 1994, several consultations were convened by the Secretary-General of the United Nations to discuss the outstanding issues regarding some aspects of the deep seabed mining provisions that inhibited some States from ratifying or acceding to the Convention. As a result of these consultations, the 1994 Agreement was adopted by the General Assembly on 28 July 1994. The representative of Fiji, Ambassador Satya N. Nandan, noted that “the Agreement had provided a practical and realistic basis for the realization of the principle of the common heritage of mankind”.18Official Records of the United Nations General Assembly, Forty-eighth Session, 99th meeting, 27 July 1994.Therein the Enterprise regime was fundamentally changed. The Enterprise was put “on hold” for the foreseeable future through the establishment of a number of conditions that must be satisfied before the Enterprise may operate as an independent entity.19Donald Rothwell, Alex Oude Elferink, Karen Scott and Tim Stephens eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 239.First, the functions of the Enterprise are to be performed by the Secretariat of the Authority until it begins to operate independently.20The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 1.Second, the question of the Enterprise functioning independently will be taken up by the Council of the Authority only upon the occurrence of one of two possible trigger events that are, respectively, the first approval of a plan of work for exploitation or, the Council’s receipt of an application for a joint venture with the Enterprise.21The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 2.If, and only if, such joint ventures are in accord with sound commercial principles, the Council shall issue a directive that provides for such independent functioning of the Enterprise.22The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 2.Moreover, the Enterprise is required to conduct its initial deep seabed mining operations only through joint ventures.23The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 2.Third, unlike Article 153, paragraph 3 of the Convention and Annex III Article 3,paragraph 5,24These two provisions provide that, except in the case of the Enterprise, the plan of work shall be in the form of a contract.the 1994 Agreement stipulates that plans of work for the Enterprise shall take the form of a contract between the Authority and the Enterprise, and the obligations applicable to other contractors are also to apply to the Enterprise.This was designed to limit any preferential treatment for the Enterprise over other mining entities. Last but not least, the 1994 Agreement relieves States Parties of any obligation to fund mine sites for the Enterprise,25The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 3.and it further established that the transfer of technology is no longer mandatory because Annex III, Article 5 of the Convention shall not apply.26The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 5.

III. Identifying Problems

Due to the fact that the 1994 Agreement effectively put the Enterprise “on hold” for the foreseeable future, no one knows how to operate the Enterprise once it becomes independent from the Authority. In this connection, a number of problems need to be resolved first.

As indicated above, there are two possible trigger events for the autonomy of the Enterprise: (a) the approval of a plan of work for the exploitation, or (b)the Council’s receipt of an application for a joint venture with the Enterprise.These two triggers are alternative. With respect to trigger “a”, at any time after the approval of the first plan of work for exploitation (Mr. Michael Lodge suggests this may refer to a plan of work for exploitation by any qualified entity, for any mineral resource),27Donald Rothwell, Alex Oude Elferink, Karen Scott and Tim Stephens eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 239.the Council may decide to allow the Enterprise to start to function independently. This issue is now reaching a critical point because, according to the “Mining Code”28The “Mining Code” refers to the whole of the comprehensive set of rules, regulations and procedures issued by the International Seabed Authority to regulate prospecting, exploration and exploitation of marine minerals in the international seabed Area. At https://www.isa.org.jm/mining-code, 26 November 2016.released by the Authority, the duration of an exploration contract normally lasts for only 15 years.29See the Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority Relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts in the Area, 16-27 July 2012, Regulation 28; Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority Relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Area, 26 April-7 May 2010, Regulation 28; Decision of the Council of the International Seabed Authority Relating to Amendments to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in the Area and Related Matters, 15-26 July 2013,Regulation 26.Upon expiration of a plan of work for exploration, the contractor shall either apply for a plan of work for exploitation, or it should have already applied for an extension of the plan of work for exploration no later than six months prior to the expiration of that plan. Otherwise, the contractor must renounce its rights in the area covered by the plan of work for exploration.

It has been 16 years since the first six contractors signed contracts with the Authority to explore polymetallic nodules in specific parts of the deep seabed in 2001. In accordance with relevant provisions, by this year, specifically, 2017,the six contractors should have either applied for a plan of work exploitation or extended the current exploration contract. In practice, from 13-24 July 2015, the Council of the Authority adopted the procedures and criteria for the extension of an approved plan of work for exploration and decided also to expedite work on a draft framework for exploitation of mineral resources in the Area.30At https://www.isa.org.jm/news/seabed-council-agrees-criteria-approved-contractextension,26 November 2016.As at 16 December 2015, all the six contractors had applied for extension of approved plans of work for exploration for polymetallic nodules.31The International Seabed Authority, ISBA/22/LTC/2, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/files/ files/documents/isba-22ltc-2_1.pdf, 26 April 2016.The reports and recommendations on each application were submitted by the Legal and Technical Commission of the Authority (LTC) in July 2016.32The International Seabed Authority, ISBA/22/LTC/2, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/files/ files/documents/isba-22ltc-2_1.pdf, 26 April 2016.On 18 July, 2016, the Council of the Authority

30 At https://www.isa.org.jm/news/seabed-council-agrees-criteria-approved-contractextension, 26 November 2016.decided to approve all the applications for extension of the contract.33The International Seabed Authority, ISBA/22/C/26-21, at https://www.isa.org.jm/consolidated-indexes/16838/60, 26 November 2016.However, it still needs to be borne in mind that the approval of an exploitation contract could happen in the foreseeable future. The Enterprise then will be activated by trigger“a”. In that case, what will the role of the Enterprise be? Obviously, pursuant to the 1994 Agreement, State Parties no longer have the obligation to fund the Enterprise,and the transfer of technology is no longer mandatory. Without capital and technology, what would the Enterprise do? Is it to supervise exploitation activities or to represent the interest of developing States? This therefore remains a tricky problem that needs to be resolved in a timely fashion.

The second problem is the relationship between the Enterprise and the developed States (including natural, judicial person or other entities which possess the nationality of the developed States or are effectively controlled by them or their nationals when sponsored by such States) or the developing States (including natural, judicial person or other entities which possess the nationality of the developing States or are effectively controlled by them or their nationals when sponsored by such States).34According to the Mining Code issued by the ISA, “States Parties, State enterprises or natural or juridical persons which possess the nationality of States or are effectively controlled by them or their nationals, when sponsored by such States, or any group of the foregoing which meets the requirements of these Regulations” all may apply to the Authority for approval of plans of work for exploration.In terms of the relationship between the Enterprise and the developed States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities), the autonomy of the Enterprise largely depends on the actions taken by the developed States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities). The reasons for this are as follows: regarding trigger“a”, normally it cannot be invoked by developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) for the lack of relevant abilities.This means that only the developed States, including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities, could possibly obtain approval for the exploitation contract and therefore give rise to the independent operation of the Enterprise. Regarding trigger “b”, the application for a joint venture operation with the Enterprise, again, it can hardly be proposed by the developing States who lack the necessary capital and technical expertise, including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities.

In 2008, Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), which was sponsored by Nauru, and Tonga Offshore Mining Limited (TOML), sponsored by Tonga,submitted their applications for the exploration of polymetallic nodules in the reserved area of the Clarion-Clipperton Fractured Zone.35The International Seabed Authority, ISBA/15/LTC.6*, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/isba-15ltc-6_1.pdf, 29 November 2016.However, it should be noted that TOML is described as “a Tongan incorporated subsidiary of Nautilus Minerals Incorporated, which holds 100 per cent of the shares of TOML through another wholly owned subsidiary, United Nickel Ltd., incorporated in Canada”.36The International Seabed Authority, SB/17/11, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/files/documents/sb-17-11.pdf, 29 November 2016.In the meantime, Nautilus and TOML are parties to a contract with NORI and NORI’s current shareholders, pursuant to which Nautilus increased its indirect ownership interest in TOML from 50% to 100% in exchange for its 50% indirect interest in NORI.37At http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/09/18/idUS132180+18-Sep-2012+MW20120918,29 November 2016.This has been observed as the new trend for the developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities)to apply for exploration rights in the reserved areas, thus bypassing the concept of a joint venture operation with the Enterprise in favour of entering into partnership with entities sponsored by developed States. The reality therefore demonstrates that the joint venture mode can hardly be proposed by the developing States(including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities). In this case the only opportunities are then left to the developed States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) that own the capital and technology to propose a joint venture operation with the Enterprise, such as the proposal from Nautilus Minerals Inc.. Following this line of consideration,the Enterprise is actually closely aligned with the developed States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities), from which it stands to obtain capital and technologies, among other benefits.

In terms of the relationships between the Enterprise and the developing States(including natural, judicial person or other entities which possess the nationality of the developing States or are effectively controlled by them or their nationals when sponsored by such States), more problems arise. The reserved areas are available only to the Enterprise by itself or in a joint venture, or to developing States(including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) in the event the Enterprise does not wish to take up the option to develop these areas.According to the “Mining Code”, the Enterprise has the first option.38The Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority Relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts in the Area, 16-27 July 2012, Regulation 18; Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority Relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Area, 26 April-7 May 2010, Regulation 18; Decision of the Council of the International Seabed Authority Relating to Amendments to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in the Area and Related Matters, 15-26 July 2013,Regulation 17.However,because of the 1994 Agreement, the Enterprise no longer avail itself of the option due to a lack of capital and technology. Thus it again is compelled to grant this right to the developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities). This conforms to the spirit of establishing the Authority and the common heritage formula. However, the recent trend of partnering with developed States (or the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) has somehow shifted the foundation of the common heritage concept. In terms of capacity building for the developing States, it was said that an application such as TOML’s was one way “of enabling developing countries to participate in activities in the Area”39Professor Frida Armas-P firter made the observation in the debate on the recommendations for approval of the application, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/sb-17-11.pdf, 29 November 2016.and “could realize meaningful participation in operations in the Area”.40The representative of the Kingdom of Tonga reminded the Council during the debate on the recommendation for approval of the application, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/files/ files/documents/sb-17-11.pdf, 29 November 2016.Still, in terms of the common heritage concept, this new way of doing business is actually contrary to the spirit of the reserved areas regime and thus delays the pace of developing common heritage concept. It is deemed that “without the Enterprise, the Area’s mineral resources could be effectively reserved for those private corporations and government entities with sufficient capital and operational knowledge to extract them, to the effective exclusion of others.”41Aline Jaeckel, Jeff A. Ardron and Kristina M. Gjerde, Sharing Benefits of the Common Heritage of Mankind-Is the Deep Seabed Mining Regime Ready?, Marine Policy, Vol. 70,2016.The involvement of developed States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) who clearly engage for their own profit in the reserved areas would lead to the result that very few developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) can benefit in this way, thus leaving many developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural,judicial person or other entities) outside the system. Considering that the reserved areas are reserved only for the Enterprise and the developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) and the common heritage concept is a justice-based approach that protects the Area and its resources from the “ first come, first served” grab,42Edwin Egede, Africa and the Deep Seabed Regime: Politics and International Law of the Common Heritage of Mankind, Heidelberg: Springer, 2011, p. 244.it can be argued that the way in which a few developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) have chosen to partner with developed States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) has somehow shifted the foundation of the common heritage concept.

Now we arrive at the third and most important problem. The foregoing discussed how the two triggers were established for the autonomy of the Enterprise.Once the Enterprise is officially established, hypothetically, what is the role of the Enterprise and how will it operate? How are the developing States going to obtain benefits from the Enterprise? In 2010 and 2012, the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Area (hereinafter “Sulphides Regulations”)43Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority Relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Area, ISBA/16/A/12/Rev.1.and the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Cobaltrich Ferromanganese Crusts in the Area (hereinafter “Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulations”)44Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority Relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts in the Area,ISBA/18/A/11.were adopted, respectively. In these regulations, an alternative to the reserved areas regime was provided by allowing contractors to elect either to provide a reserved area or to offer an equity interest in a future joint venture with the Enterprise.45Regulation 16 of both documents is identical which provides that “Each applicant shall, in the application, elect either to: (a) Contribute a reserved area to carry out activities pursuant to article 9 of annex III to the Convention, in accordance with regulation 17; or (b) Offer an equity interest in a joint venture arrangement in accordance with regulation 19.”Since then, many State and non-State entities sponsored by States, such as Brazil,46See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/brazil-applies-approval-plan-workexploration-cobalt-rich-ferromanganese-crust, 29 November 2016.India,47See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/india-applies-approval-plan-workexploration-polymetallic-sulphides, 29 November 2016.China,48See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/comra-applies-approval-plan-workexploration-polymetallic-sulphides, 29 November 2016.the Russian Federation,49See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/russian-federation-applies-approval-planwork-exploration-polymetallic-sulphides, 29 November 2016.Japan50See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/international-seabed-authority-receives-twonew-applications-seabed-exploration, 29 November 2016.and Germany51See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/germany-applies-approval-plan-workexploration-polymetallic-sulphides, 29 November 2016.have all opted to offer an equity interest in a future joint venture arrangement with the Enterprise in lieu of providing a reserved area. This option has resulted in a considerable decrease in the amount of reserved areas available, however – theoretically at least – at the same time the Enterprise has been enabled to participate in more activities in the deep seabed.

Yet it remains largely unknown how the Enterprise will benefit from such an uncertain future joint venture. According to Regulation 19 of both the Sulphides Regulations and the Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulations, the Enterprise shall obtain a minimum of 20 percent of the equity participation in the joint venture arrangement, of which 10 percent shall be obtained without payment. Additionally,a further thirty percent of the equity in the joint venture arrangement, or such lesser percentage, shall be offered to the Enterprise for purchase. The additional thirty percent, or less, equality participation is illustrated in a footnote that reads, “the terms and conditions upon which such equity participation may be obtained would need to be further elaborated.” The foregoing demonstrates that the Enterprise will play an important role in the future activities of the deep seabed. But there are many unanswered questions. How is the Enterprise, for example, to acquire additional equity when it has no capital or definite means of capital raising? Although the problem may seem some years away, the question of how to build a model for the operation of the Enterprise should be solved as a matter of urgency.

IV. The Way Forward

In 2013, the ISA Council requested the Secretary-General, referring where appropriate to the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) and the Finance Committee, to carry out a study of the issues relating to the operation of the Enterprise, in particular on the legal, technical and financial implications for the Authority and for States Parties, taking into account the provisions of the Convention, the 1994 Agreement and the Regulations.52See the International Seabed Authority, ISBA/19/C/18, para. 16, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/isba-19c-18_0.pdf, 29 November 2016.Accordingly, the operation of the Enterprise has been on the agenda of the LTC ever since.53See the International Seabed Authority, ISBA/20/LTC/1, para. 12(d), at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/isba-20ltc-1_0.pdf, 29 November 2016. Also see the International Seabed Authority, ISBA/22/LTC/1, para. 16, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/isba-22ltc-1_1.pdf, 29 November 2016.The document issued in 2014 demonstrates that a few studies have been done, especially,preparing the draft terms of reference to guide and assist further research on the issue.54See the International Seabed Authority, ISBA/20/LTC/12, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/ files/ files/documents/isba-20ltc-12_0.pdf, 29 November 2016.Still, not much has been done relating to the operation of the Enterprise.It is stated that “the implications of a potential failure to establish a functioning Enterprise have not yet been properly discussed – either within the ISA or the UN General Assembly.”55Aline Jaeckel, Jeff A. Ardron and Kristina M. Gjerde, Sharing Benefits of the Common Heritage of Mankind-Is the Deep Seabed Mining Regime Ready?, Marine Policy, Vol. 70,2016.The Authority is in the process of developing regulations for the exploitation of mineral resources in the Area. And in March 2015, two consultation documents were issued that are, respectively, Draft Framework for the Regulation of Exploitation Activities and Discussion Paper on the Financial Terms of Exploitation Contracts.56At https://www.isa.org.jm/legal-instruments/ongoing-development-regulations-exploitationmineral-resources-area, 29 November 2016.In the report containing a draft framework for the regulation of exploitation activities in the Area, it was clarified that “as noted in the Executive summary, there are four areas of the regulatory framework that are not addressed in this Section 2, being: … 4. The operation and effective participation of the Enterprise. It is not the intention of the Commission to undertake further work in respect of 2, 3 and 4 above at this time.”57Developing a Regulatory Framework for Mineral Exploitation in the Area – Report to Members of the Authority and All Stakeholders, Section 2, p. 4, at https://www.isa.org.jm/files/documents/EN/Survey/Report-2015.pdf, 29 November 2016.Also, the subject of equity interest in a joint venture arrangement, together with an action plan for operationalization of the Enterprise, are all classified as priority C, which means that there was no anticipated action at the time the report was prepared.58Developing a Regulatory Framework for Mineral Exploitation in the Area – Report to Members of the Authority and All Stakeholders, Section 5, p. 46.It thus can be seen that a substantial study regarding the operation of the Enterprise should be conducted,even if with the 2016 extensions of the contracts for exploration until at least 2021,it may seem less urgent.

One aspect of this inquiry is certain and that is that we cannot forget about the Enterprise. Regulation 19 of both the Sulphides Regulation and the Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulation shows that the Enterprise will play an important role in future activities in the deep seabed. Furthermore, regarding the reserved area regime, the Enterprise also cannot be ignored. It is clear that the reserved area is reserved for the developing States (including the foregoing mentioned natural, judicial person or other entities) and the Enterprise. The Enterprise has the first option to choose.59Article 9 of Annex III to the Convention provides that “the Enterprise shall be given an opportunity to decide whether it intends to carry out activities in each reserved area.”Pursuant to the 1994 Agreement, section 2, paragraph 5, a contractor that has contributed a reserved area to the Authority has the right of first refusal to enter into a joint venture arrangement with the Enterprise for the exploration and exploitation of the area. The same provision could be found in Regulation 18 of both the Sulphides Regulation and the Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulation, paragraphs 3 and 4. It is further stipulated:

If the Enterprise or a developing State or one of the entities referred to in paragraph 1 does not submit an application for approval of a plan of work for exploration for activities in a reserved area within 15 years of the commencement by the Enterprise of its functions independent of the Secretariat of the Authority or within 15 years of the date on which that area is reserved for the Authority, whichever is the later, the contractor whose application for approval of a plan of work for exploration originally included that area shall be entitled to apply for a plan of work for exploration for that area provided it offers in good faith to include the Enterprise as a joint-venture partner.

Again, a joint venture with the Enterprise is highlighted in the case of reversion of reserved areas.

The next few years present a unique opportunity to move forward to address the problems relating to the independent operation of the Enterprise. Firstly, what urgently needs to be solved is how the Enterprise should be operated. We should always bear in mind that the Enterprise was primarily established to represent the interests of developing States in the reserved areas. The recent practice has shown a trend of selective use of reserved areas. Starting from NORI, whose application area was divided into four regions,60See ISA news, at https://www.isa.org.jm/news/seabed-authority-and-nauru-ocean-resourcesinc-sign-contract-exploration, 29 November 2016.the exploration contract that was signed between the Authority and Marawa Research & Exploration Ltd.,a company sponsored by another small island developing State, the Republic of Kiribati, covered three regions in three blocks in 2015.61See ISA news, https://www.isa.org.jm/news/isa-and-marawa-research-exploration-ltd-signexploration-contract-polymetallic-nodules-reserved, 29 November 2016.However, the most obvious case demonstrating the trend is the 2015 application of China Minmetals Corporation, sponsored by China, whose application area was divided into eight blocks.62See China Minmetals Corporation news, at http://www.minmetals.com.cn/wkxw/201507/t20150722_118356.html, 29 November 2016. (in Chinese)This could lead to the problem that the remaining areas are too small and therefore rendered useless. Additionally, in July 2012, the Authority adopted an environmental management plan of designating a network of Areas of Particular Environmental Interest (APEI) in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.63Decision of the Council Relating to an Environmental Management Plan for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, ISBA/18/C/22, at https://www.isa.org.jm/sites/default/files/files/documents/isba-18c-22_0.pdf, 29 November 2016.The designation of APEIs, although it was implemented on a provisional basis, could make it impossible to undertake activities effectively in the reserved areas. In this manner,even upon the immediate autonomy of the Enterprise, it would hardly leave anything valuable to explore. Considering that the offering of reserved areas is decreasing, it makes better sense if the Enterprise could focus on mining activities beyond the reserved areas, which requires a powerful Enterprise in terms of both capital and technology. The 1994 Agreement, Section 2, paragraph 2 stipulates that“[T]he Enterprise shall conduct its initial deep seabed mining operations through joint ventures.” Moreover, given the fact that lots of countries, natural, judicial person or other entities choose the joint venture arrangement in lieu of providing reserved areas according to Regulation 16 of both the Sulphides Regulation and the Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulation, there is huge potential for the Enterprise to conduct mining activities through joint ventures. Considering that the equity interest arrangement in the joint venture is still unknown and the action plan for operationalization of the Enterprise has not yet been developed, it would be rewarding to study how the Enterprise can fit itself into the joint venture to conduct exploration or exploitation in the deep seabed. Reading Regulation 19 of both the Sulphides Regulation and the Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulation,which stipulates that the Enterprise shall obtain a minimum of 20 percent of the equity participation in the joint venture arrangement and a further 30 percent of the equity in the joint venture arrangement, or such lesser percentage, shall be offered to the Enterprise to purchase, we can see that the international market rules and the economy will play a leading role, nevertheless, may thus compromising the“common heritage of mankind” principle.

Availability of funds, access to technology, resources and metal market would be the most important and practical issues to be considered for the operation of the Enterprise.64Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, pp. 62~74.Regarding availability of funds, the Enterprise is supposed to derive its funds from the following sources: amounts received from the ISA;65Article 11(1)(a), Annex IV, the Convention.voluntary contributions made by States Parties;66Article 11(1)(b), Annex IV, the Convention.income derived by the Enterprise through its operation67Article 11(1)(d), Annex IV, the Convention.and amounts borrowed by the Enterprise.68Article 11(2)(a), Annex IV, the Convention.In contrast with Annex IV,the 1994 Agreement waives the obligation of States Parties to provide interest-free long-term loans in financing the Enterprise.69The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 2, para. 4.The financial provisions under the Convention were intended to put the Enterprise in a favourable position where it would have been able to compete with other operators, while the 1994 Agreement has in essence placed the Enterprise in a position of disadvantage.70Edwin Egede, Africa and the Deep Seabed Regime: Politics and International Law of the Common Heritage of Mankind, Heidelberg: Springer, 2011, p. 179.Regarding access to technology, the 1994 Agreement declares that the mandatory provisions on transfer of technology under Article 5 of Annex III “shall not apply” and such technology shall be obtained on fair and reasonable commercial terms on the open market, or through joint-venture arrangements.71The 1994 Agreement, Annex, Section 5, para. 1(a).In this way, the 1994 Agreement witnessed a swing from the position of mandatory transfer of technology to a position that merely required cooperation and has eroded any perceived advantage that developing States would derived from the provisions of the Convention on the transfer of technology.72Edwin Egede, Africa and the Deep Seabed Regime: Politics and International Law of the Common Heritage of Mankind, Heidelberg: Springer, 2011, pp. 97~98.With respect to access to resources, as mentioned,the reserved areas are reserved only for the Enterprise and the developing States.Only when the Enterprise decides not to use a reserved area, may it be given to a developing State or an entity of it for use.73Convention, Article 9, Annex III. See also Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, p. 69.Thus acquisition of reserved areas is an effective and economic way to gain access.74Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, p. 69.Furthermore, nothing in the Convention prevents the Enterprise from conducting prospecting as an additional means to discover more mine sites which may also be kept in reserve for the Enterprise.75Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, p. 69.Last but not least, access to metal market which demands on the interplay of three basic factors: the future demand for metal; the volume of supply from land based mining; and the economic competitiveness of metal mining, would be difficult and complicated to estimate without reliable basic data.76Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, p. 69.However,apart from commercial reasons, various factors may enter into the decision making process of the Enterprise concerning going into seabed mining.77Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, p. 69.It is said that“[i]t may be argued that the participation of the developing countries and the training of their personnel in seabed mining are also compelling reasons for the Enterprise to go into seabed mining. Presumably, these are reasons complementary to, rather than substituting for, the commercial reason.”78Roy S. Lee, The Enterprise: Operational Aspects and Implications, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 1980, p. 69.

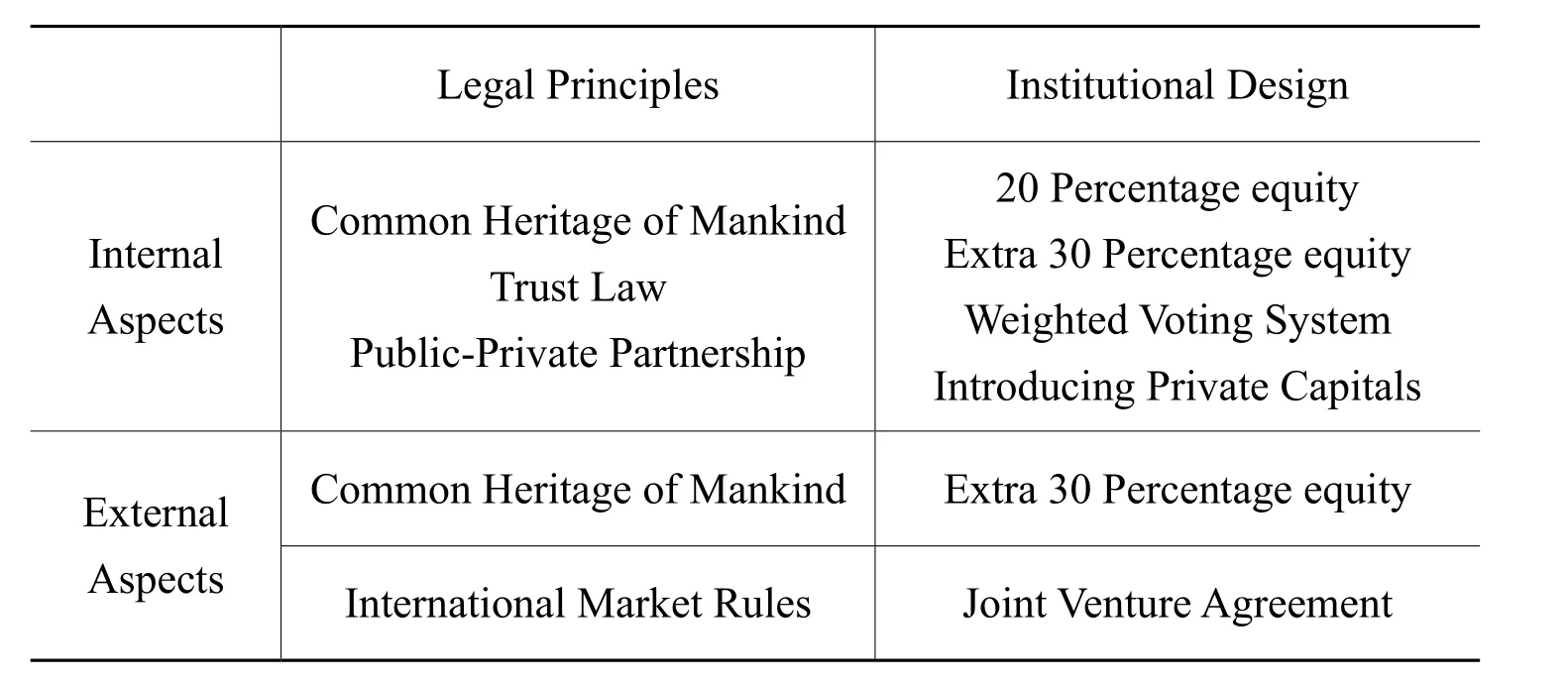

When analyzing the operationalization of the Enterprise, two issues should be evaluated: one is internal, and the other is external. Given that the Enterprise was first established to represent the interests of developing States, including the landlocked and geographically disadvantaged among them, the internal aspect would focus on institutional design in terms of legal system, organizational framework,funding mechanism and supervision coordination. Most importantly, a few legal principles and corresponding institutional designs should be highlighted.

The first issue relating to the internal aspect is, indisputably, the “common heritage of mankind” principle. It is difficult to define the scope and content of the obligation and responsibility that the phrase may encompass.79Michael W. Lodge, The Common Heritage of Mankind, The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 2012, p. 734. Also see Edwin Egede, Africa and the Deep Seabed Regime: Politics and International Law of the Common Heritage of Mankind, Heidelberg:Springer, 2011, pp. 60~64.As far as the deep seabed is concerned, activities therein shall be carried out for the benefit of mankind as a whole.80The Convention, Article 140.The Enterprise, as it represents the interests of developing States, including the land-locked and geographically disadvantaged among them,would act as a kind of trustee.81Trustee is one who holds the legal title to property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility for the benefit of another. The trustees administer the affairs attendant to the trust. See Henry Campbell Black, Black’s Law Dictionary, Fifth Edition, St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1979, p. 1357.This is not a novel concept in the way of governing activities in the Area. In 1967 Ambassador Pardo put forward the idea of trustee in the Area by saying that “[w]e envisage such an agency [the Authority] as assuming jurisdiction, not as a sovereign, but as a trustee for all countries over the oceans and the ocean floor. The agency should be endowed with wide powers to regulate,supervise and control all activities on or under the oceans and the ocean floor.”82United Nations General Assembly, UNGA, UN Doc A/C.1/PV.1516, 1 November 1967, para. 8, at https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/NL1/556/09/PDF/NL155609.pdf?OpenElement, 28 April 2016. Also see Aline Jaeckel, Jeff A. Ardron and Kristina M. Gjerde, Sharing Benefits of the Common Heritage of Mankind-Is the Deep Seabed Mining Regime Ready?, Marine Policy, Vol. 70, 2016.The beneficiaries,83Beneficiary is one who benefits from act of another. See Henry Campbell Black, Black’s Law Dictionary, Fifth Edition, St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1979, p. 142.which are more like third party beneficiaries,84Third party beneficiary is one for whose benefit a promise is made in a contract but who is not a party to the contract. See Henry Campbell Black, Black’s Law Dictionary, Fifth Edition, St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1979, p. 1327.are developing States, including the land-locked and geographically disadvantaged among them.As trustee, the Enterprise is obligated to make the trust property productive.85Developments in the Law: Trusts – 1934, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 48, No. 7, 1935, p.1181.In order to achieve that purpose, the Enterprise needs to act creatively and take initiatives to mobilize various resources. As for the internal institutional design, the weighted voting system of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) can be adapted into the operation of the Enterprise in many ways. Again according to Regulation 19 of both the Sulphides Regulation and the Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulation, the Enterprise shall obtain a minimum of 20 percent of the equity participation in the joint venture arrangement and a further 30 percent of the equity in the joint venture arrangement, or such lesser percentage can be purchased.Because the above-stated 20 percent of equity is inherently provided to the Enterprise, inside the Enterprise, the developing States, including the land-locked and geographically disadvantaged among them, can equally share the equity interests, if there are any. This also conforms to the spirit of the “common heritage of mankind” principle. Additionally, a type of weighted voting system could be introduced to solve the funding problem relating to the extra purchasable equity.Those States that are willing to offer more capital to the Enterprise in purchasing the extra 30 percent, or less, equity should possibly profit more from the activities that are conducted by the joint ventures. In this way, there is a chance for the Enterprise to actively participate in mining operations through joint ventures.Furthermore, due consideration could be paid to the theory of “public-private partnership” (PPP) as well. PPP is a label that is used to describe a broad range of relationships between public and private entities.86Julia Paschal, Public-Private Partnerships, Procurement Lawyer, Vol. 44, Issue 1, 2008, p. 9.Specifically, it means a State relies on private actors instead of government employees to deliver certain infrastructure and services to the public.87Dominque Custos and John Reitz, Public-Private Partnerships, American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 58, Issue-Supplement, 2010, p. 556.It is said that “through PPP, private and public entities have combined their expertise and experience to finance public projects using all available resources, reconciling often conflicting requirements to weave together enough present and future money to both accomplish the goals of the public sector and provide a profit incentive to private sector participants.”88Julia Paschal, Public-Private Partnerships, Procurement Lawyer, Vol. 44, Issue 1, 2008, p.10.For the operation of the Enterprise, private capital can be introduced through various economically viable forms as long as contracts or agreements can be concluded.The terms and conditions of the contracts or agreements would need to be further elaborated.

As for the external aspect regarding the operationalization of the Enterprise,the relationship between the applicant who chooses the joint venture arrangement in lieu of providing reserved areas and the Enterprise is the priority of the analysis.Given that there will be a joint venture agreement between an applicant and the Enterprise, it would be much easier to be dealt with. The agreement will be the blueprint upon which any future cooperative action will be based. It further needs to be noted that the extra 30 percentage purchasable equity as provided in Regulation 19, paragraph (b) of both the Sulphides Regulation and the Cobaltrich Ferromanganese Crusts Regulation, once again demonstrates the “common heritage of mankind” principle is applicable to the external aspects regarding the operationalization of the Enterprise.

Legal Principles Institutional Design Internal Aspects Common Heritage of Mankind Trust Law Public-Private Partnership 20 Percentage equity Extra 30 Percentage equity Weighted Voting System Introducing Private Capitals External Aspects Common Heritage of Mankind Extra 30 Percentage equity International Market Rules Joint Venture Agreement

V. Conclusion

The Enterprise regime was intensively negotiated first in the UNCLOS III from 1973 to 1982 and then equally intensively diluted in the Secretary General’s informal consultations from 1990 to 1994. The Convention and the 1994 Agreement are two major achievements. From the Convention to the 1994 Agreement, the Enterprise regime has been radically affected in many ways, for instance, the autonomy of the Enterprise has been put “on hold”, the obligation of States Parties to fund mine sites for the Enterprise has been relieved, and the transfer of technology is no longer mandatory. The reason for these changes is described as “the industrialized countries had long regarded the provisions of the LOSC as unworkable and particularly objected to any suggestion that they would be responsible for financing the initial operation of the Enterprise.”89Donald Rothwell, Alex Oude Elferink, Karen Scott and Tim Stephens eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 238~239.

Envisaged as an operational organ of the Authority, the outlook of the Enterprise is still unknown. A few questions need to be answered urgently. In terms of the institutional design, attention should be paid to two parallel issues,one being internal and the other being external. Internal aspects pertain to the organizational framework, the funding mechanism and supervision coordination.Most importantly, a few legal principles and corresponding institutional designs should be highlighted. Other than the “common heritage of mankind” principle, the international market rules, trust law and the public-private partnership concept all could be adapted to the development of the institutional design of the Enterprise.The external aspects mainly center on the relationship between the Enterprise and the applicant. Compared with the internal issues, it is less complicated due to the joint venture agreement, which serves as the blueprint that any future cooperative action will base on. International market rules will play a prominent role during the implementation of the joint venture agreement. Considering that the study on the legal, financial, administrative issues associated with the Enterprise is insufficient,further inputs and considerations should be provided, and the ISA should get on with its work in this respect as a matter of urgent when drafting the exploitation regulations or in its next 3-5 years work programme.