Hepatitis B virus markers in hepatitis B surface antigen negative patients with pancreatic cancer: Two case reports

Sergey Batskikh, Sergey Morozov, Dmitry Kostyushev

Sergey Batskikh, Department of Hepatology, Moscow Clinical Research Center named after A.S. Loginov, Moscow 111123, Russia

Sergey Morozov, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Federal Research Center of Nutrition and Biotechnology, Moscow 115446, Russia

Dmitry Kostyushev, Laboratory of Genetic Technologies, Martsinovsky Institute of Medical Parasitology, Tropical and Vector-Borne Diseases, First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow 119991, Russia

Dmitry Kostyushev, Division of Biotechnology, Sirius University of Science and Technology, Sochi 354340, Russia

Abstract BACKGROUND Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a known carcinogen that may be involved in pancreatic cancer development. Detection of HBV biomarkers [especially expression of HBV regulatory X protein (HBx)] within the tumor tissue may provide direct support for this. However, there is still a lack of such reports, particularly in non-endemic regions for HBV infection. Here we present two cases of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, without a history of viral hepatitis, in whom the markers of HBV infection were detected in blood and in the resected pancreatic tissue.CASE SUMMARY The results of examination of two patients with pancreatic cancer, who gave informed consent for participation and publication, were the source for this study. Besides standards of care, special examination to reveal occult HBV infection was performed. This included blood tests for HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs, HBV DNA, and pancreatic tissue examinations with polymerase chain reaction for HBV DNA, pregenomic HBV RNA (pgRNA HBV), and covalently closed circular DNA HBV (cccDNA) and immunohistochemistry staining for HBxAg and Ki-67. Both subjects were operated on due to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and serum HBsAg was not detected. However, in both of them anti-HBc antibodies were detected in blood, although HBV DNA was not found. Examination of the resected pancreatic tissue gave positive results for HBV DNA, expression of HBx, and active cellular proliferation by Ki-67 index in both cases. However, HBV pgRNA and cccDNA were detected only in case 1.CONCLUSION These cases may reflect potential involvement of HBV infection in the development of pancreatic cancer.

Key Words: Pancreatic cancer; Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; Hepatitis B virus; Previous hepatitis B; Anti-HBc; Hepatitis B virus X antigen

lNTRODUCTlON

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide and its incidence rate is growing[1]. Among different types of pancreatic cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma represents 90% of cases[2]. Despite difference in epidemiology observed across regions (incidence rates of 0.5-9.7 per 100000 people), it causes about 4% of all deaths per year globally[2]. PC is known for its aggressive nature with a low 5-year survival rate that does not exceed 9%[3].

Early detection of PC remains a challenge. Therefore, stratification of risk factors and identification of subjects at risk are actual. The known risk factors for PC are male sex, non-O (I) blood group, cigarette smoking, low physical activity, genetics and positive family history, presence of diabetes mellitus, obesity, dietary factors (high levels of red and processed meat, low fruits and vegetables consumption, and alcohol intake), and history of pancreatitis[4]. Association of PC with some infections, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, has been described[5,6]. However, the results of these reports are controversial, and the mechanisms of HBV involvement in pathogenesis of PC are not fully clear.

HBV is a known carcinogen that causes up to 80% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma in endemic regions[7]. Also, the virus may be involved in non-liver oncogenesis due to its ability to integrate into the genome of infected cells, to cause genomic aberrations and enhance expression of oncogenes or inhibit tumor suppressors[8]. Several reports have shown that replication of the virus may occur not only in the liver, but also in other organs, including the pancreas[9-11]. Moreover, pancreatic beta cells and hepatocytes develop from the ventral foregut endoderm during ontogenesis and thus may share characteristics favorable for HBV-induced tumor development[12]. Markers of previous or current HBV infection are commonly found in patients with PC, while HBV DNA and viral antigens have been detected in the pancreatic tumor tissues, suggesting a potential role of the infection in the etiology of this cancer[13-15]. However, most of these reports came from Asian countries, where HBV infection is prevalent, and most of subjects were HBsAg-positive. In contrast, uncertain results of the cohort studies performed in Europe (1 from Denmark and 2 from Sweden) make an association of the PC and HBV infection questionable[5,16-18]. Although the data of epidemiological studies are important, direct support of the involvement of HBV infection in PC development may be provided with the detection of HBV biomarkers [especially expression of HBV regulatory X protein (HBx)] within the tumor tissue. However, there is still a lack of such reports, especially in non-endemic regions for HBV infection.

Here we report two cases of patients with no history of HBV infection, admitted to the Moscow Clinical Research Center named after A.S. Loginov for pancreatic cancer treatment, who gave their consent for special examination and the use of the obtained data for scientific purposes, including publication of images.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

Case 1:The patient was a 61-year-old white/Caucasian man, with blood type O (I). His complaints were non-remarkable.

Case 2: The patient was a 60-year-old white/Caucasian man, with blood type A (II) with no remarkable complaints.

History of present illness

Case 1:The patient was admitted for planned surgery in June 2019. Previous repeated screening blood tests on HBsAg were negative.

Case 2:The patient was admitted in February 2020 for planned surgical treatment due to previously diagnosed pancreatic cancer involving the superior mesenteric vein. Before surgery, he received seven courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy according to the FOLFIRINOX scheme with no progression of the tumor.

History of past illness

Case 1:The patient’s history of past illness was non-remarkable.

Case 2:The patient had a known history of chronic pancreatitis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obesity (body mass index 34.5 kg/m2).

Personal and family history

Case 1:The patient had a history of alcohol abuse.

Case 2:The patient had a personal history of alcohol abuse and smoking experience for more than 20 years.

Physical examination

Cases 1 and 2:No notable deviations.

Laboratory examinations

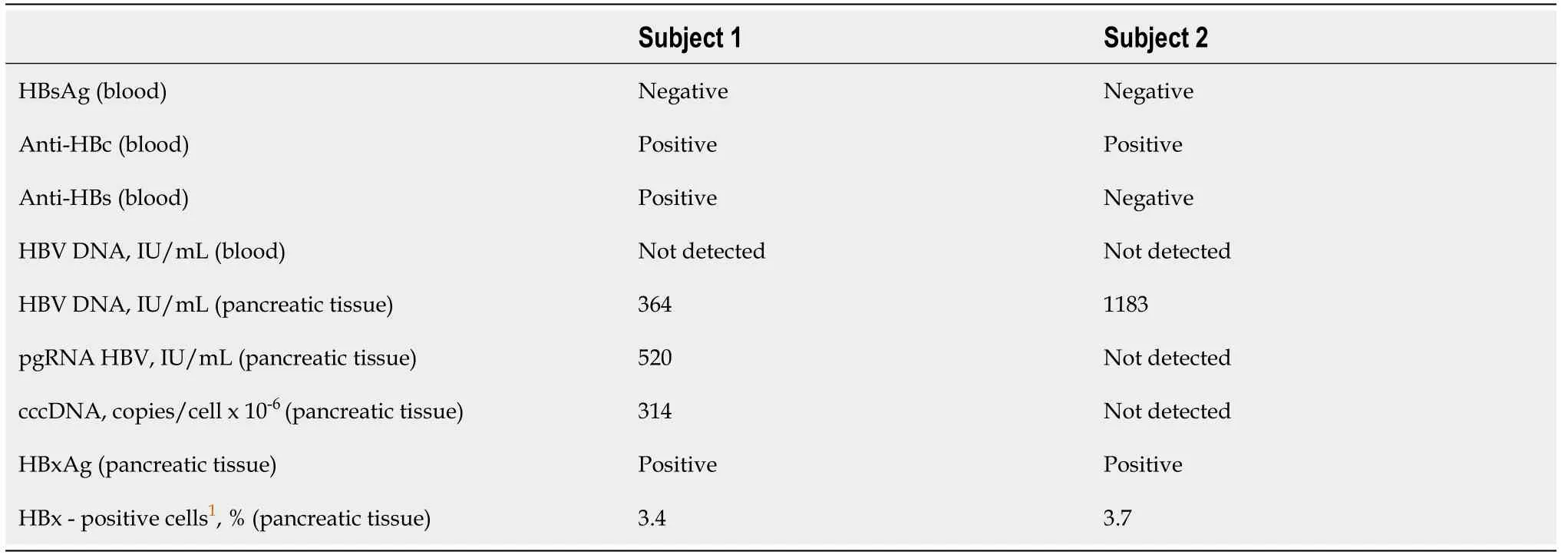

Case 1:At admission, blood tests revealed signs of previous hepatitis B, but no markers of current HBV infection (Table 1). Methods used for standard and special examinations are described in Supplementary material[19-20].

Histological assessment of the resected tissue revealed ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (pT1 G2 R0 N0 V0 Pn0)[21,22].

Case 2:At admission, no markers of current HBV infection were detected by blood tests. However, serum anti-HBc test was positive, suggesting that the patient had a previous hepatitis B (Table 1).

Morphological examination of the resected tissue identified pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with involvement of the duodenal wall (pT2 R0 N0 V0 Pn1 TRS 3)[21,22].

Imaging examinations

Case 1:Special examination of the resected pancreatic tissue in this case revealed markers of HBV replication and active cellular proliferation, as well as expression of HBx (shown in Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1 Results of special examination of blood and pancreatic tissue samples

Case 2:Examination of the resected pancreatic tissue gave positive result for HBV DNA, with no other markers of active viral replication (Table 1). However, immunohistochemistry revealed expression of HBx and high level of cellular proliferation by Ki-67 index (Table 1 and Figure 1).

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

In both cases, based on result of a complex examination, cancer of the head of the pancreas was diagnosed.

TREATMENT

Case 1:The patient underwent laparoscopic distal subtotal pancreatic resection with resection of the splenic vessels using the Warshaw technique.

Case 2:The patient underwent gastropancreatoduodenal resection.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Cases 1 and 2:After discharge, both patients continued treatment offered by a local oncologist. No special treatment for silent HBV infection was required. The patients were advised to undergo regular check-ups to exclude reactivation of HBV infection: Alanine aminotransferase, HBsAg, and HBV DNA (in blood) at least once in 3 mo.

DlSCUSSlON

These two cases demonstrate the presence of HBV markers in HBsAg-negative patients with pancreatic cancer in non-endemic regions for the infection. Both of our patients had several known risk factors for PC development. We suppose that previous HBV infection could be an additional risk factor for PC. It is known that HBV infection, even resolved, may present a molecular basis for carcinogenesis. Carcinogenic mechanisms in HBsAg-negative persons with previous HBV infection may be related to transcriptional activity of episomal HBV genomes (cccDNA), which remains in the cell nucleus as a matrix for the life-long synthesis of new virions. In case 1, detection of not only HBV DNA but also cccDNA and pgRNA HBV (transcribed exclusively from cccDNA) suggests that this patient had a silent low-level replication of the virus in the pancreatic tissue. In case 2, pgRNA HBV and cccDNA were not detected despite a significant amount of HBV DNA in the pancreatic tissue. While no HBV replication in this patient was found, integrated HBV DNA could evidently cause the expression of HBx, which is similar to that observed in hepatocellular cancer[23]. This protein, detected in pancreatic tissue of both of our subjects, is considered to be the most pro-oncogenic[24]. It is assumed that HBx plays a major role in pathogenesis of liver cancer through nuclear translocation, protein-protein interactions, influence on transcription regulation, induction of chromosomal instability, control of proliferation, and transformation, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells even in cases when HBV replication is absent[23,24]. These mechanisms may also play a role in extra-hepatic cancer development. To our knowledge, there are only two studies that described HBx expression in pancreatic cancer tissues, both performed in a cohort of Asian patients in HBV endemic regions[11,25]. Songet al[11] reported that HBx expression was detected in ten out of ten subjects with PC and only three were HBsAg-negative.

Although the presence of HBV biomarkers in pancreatic adenocarcinoma tissue detected by PCR and immunohistochemistry does not allow proving causal relationship between the two conditions, it reflects potential involvement of the virus in the etiology and pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer. It may be important that Ki-67 proliferative index was more than 50% in both subjects. According to the literature, such values are relatively rare among PC patients (approximately 12%), and associated with more aggressive grade and poorer prognosis[20].

Together with data of the cohort studies, our cases may be important for the clinical practice. It is not yet clear whether universal testing of all patients with PC for anti-HBc and HBV DNA is necessary. However, these tests are reasonable when chemotherapy is planned, and when blood transaminases flare on the mentioned treatment occurs[26,27].

Detection of HBV cccDNA in pancreatic tissue in HBsAg-negative subject in our report may support the need for revision of the statements of the Taormina Workshop (2018), which defines occult HBV infection as the presence of replication-competent HBV DNA in the liver and/or HBV DNA in the blood of people who test negative for HBsAg[28]. As extrahepatic replication of HBV DNA may occur in HBsAg-negative subjects (as shown in a number of studies and in our case 1), skipping a mention of specific organ for HBV DNA (cccDNA) detection seems reasonable.

CONCLUSlON

The described cases may reflect potential involvement of HBV infection in the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Larger studies are necessary to assess the risk of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in subjects with previous HBV infection and define HBV-associated mechanisms of cancerogenesis in them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the subjects who gave their consent for participation and preparation of these cases.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Batskikh S collected the data; Batskikh S and Morozov S analyzed the data; Kostyushev D performed PCR and immunohistochemistry, and prepared the figures; Morozov S and Batskikh S drafted the manuscript; all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Supported bythe Ministry of Science and Higher Education, No. FGMF-2022-0005; the Russian Science Foundation, No. 20-15-00373; and the Moscow Healthcare Department, No. AAAA-A18-118021590196-1.

lnformed consent statement:The participants provided written informed consent for examination beyond standards of care and use their data for scientific purposes, including publication, prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement:Dr. Morozov reports grants from Russian Science Foundation, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from AlfaSigma, non-financial support from Laborie, personal fees from DrFalk, personal fees from Takeda, and other from Federal Research Center of Nutrition and Biotechnology, outside the submitted work. Dr. Batskikh reports personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from MSD, and personal fees from R-PHARM, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kostyushev reports grants from Russian Science Foundation, within submitted work. All authors declare no competing interests.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:All authors have read the CARE statement - checklist of items and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to CARE statement - checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Russia

ORClD number:Sergey Batskikh 0000-0002-5917-203X; Sergey Morozov 0000-0001-6816-3058; Dmitry Kostyushev 0000-0002-1851-7441.

S-Editor:Wang LL

L-Editor:Wang TQ

P-Editor:Wang LL

World Journal of Hepatology2022年7期

World Journal of Hepatology2022年7期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Retraction Note: Screening and identification of bioactive compounds from citrus against non-structural protein 3 protease of hepatitis C virus genotype 3a by fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay and mass spectrometry

- Challenge of managing hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections in resource-limited settings

- Gut microbiota contribution to hepatocellular carcinoma manifestation in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- “Starry liver” - Von Meyenburg complex clinical case presentation and differential diagnosis discussion: A case report

- Volumetric assessment of hepatic grafts using a light detection and ranging system for 3D scanning: Preliminary data

- Hepatitis C virus burden: Treating and educating people without prejudice