Analysis of the effect of repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming point on electroencephalograms

Xin Zhang, Lingdi Fu, Yuehua Geng, Xiang Zhai, Yanhua Liu

1 Tianjin Polytechnic University, Tianjin, China

2 Province-Ministry Joint Key Laboratory of Electromagnetic Field and Electrical Apparatus Reliability, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, China

3 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Tianjin Huanhu Hospital, Tianjin, China

4 Hebei College of Industry and Technology, Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, China

Analysis of the effect of repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming point on electroencephalograms

Xin Zhang1, Lingdi Fu2, Yuehua Geng2, Xiang Zhai3, Yanhua Liu4

1 Tianjin Polytechnic University, Tianjin, China

2 Province-Ministry Joint Key Laboratory of Electromagnetic Field and Electrical Apparatus Reliability, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, China

3 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Tianjin Huanhu Hospital, Tianjin, China

4 Hebei College of Industry and Technology, Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, China

Here, we administered repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation to healthy people at the left Guangming (GB37) and a mock point, and calculated the sample entropy of electroencephalogram signals using nonlinear dynamics. Additionally, we compared electroencephalogram sample entropy of signals in response to visual stimulation before, during, and after repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming. Results showed that electroencephalogram sample entropy at left (F3) and right (FP2) frontal electrodes were significantly different depending on where the magnetic stimulation was administered. Additionally, compared with the mock point, electroencephalogram sample entropy was higher after stimulating the Guangming point. When visual stimulation at Guangming was given before repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation, signi fi cant differences in sample entropy were found at fi ve electrodes (C3, Cz, C4, P3, T8) in parietal cortex, the central gyrus, and the right temporal region compared with when it was given after repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation, indicating that repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at Guangming can affect visual function. Analysis of electroencephalogram revealed that when visual stimulation preceded repeated pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation, sample entropy values were higher at the C3, C4, and P3 electrodes and lower at the Cz and T8 electrodes than visual stimulation followed preceded repeated pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. The fi ndings indicate that repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming evokes different patterns of electroencephalogram signals than repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at other nearby points on the body surface, and that repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming is associated with changes in the complexity of visually evoked electroencephalogram signals in parietal regions, central gyrus, and temporal regions.

nerve regeneration; brain injury; acupuncture; magnetic stimulation; acupuncture point; mock point; Guangming point; brain function; electroencephalogram signals; complexity; sample entropy; nonlinear dynamics; NSFC grant; neural regeneration

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 31100711, 51377045, 31300818; the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province, No. H2013202176.

Zhang X, Fu LD, Geng YH, Zhai X, Liu YH. Analysis of the effect of repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming point on electroencephalograms. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9(5):549-554.

Introduction

Acupuncture therapy is an in vitro means of regulating the body’s functions and treating diseases through stimulation. Acupoints are nerve-sensitive regions found in Chinese medicine (NIH, 1997; Maciocia, 2005). As modern scienti fi c techniques in meridian research develop, accumulated evidence has begun to reveal mechanisms underlying acupuncture therapy, and explain the essence of acupuncture points and meridians in a modern scientific and intuitive way (Li et al., 2008; You et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Stimulation at acupoints has a positive impact on nerve regeneration. For example, electric acupuncture promoted the regeneration of different fi ber components in tibial nerves (Kong et al., 1993), and signi fi cantly up-regulated the expression of nerve growth factor in mimetic muscle tissue during facial nerve regeneration (Ya et al., 2000).

Magnetic stimulation is a relatively new acupuncture stimulation-therapy with incomparable advantages (Yu et al., 2011). Growing evidence has focused on cell physiology and transmission of neural signals under a magnetic fi eld. Static magnetic fields are thought to be a potential non-invasive treatment for Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders. For instance, a 100–1,000 mT static magnetic fi eld reproduced the cellular effects of ZM241385 (a candidate drug for Parkinson’s disease) in cultured rat-PC12 cells (Wang et al., 2010). Moderate-strength static magnetic fi elds can alsocause apparent alterations in action potentials, half-activation voltage, and slope factor. As evidenced by the reduction of neural recti fi er-potassium channels (Li et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010). Using independent component analysis, Spasic et al. (2011) analyzed the sources of fractal complexity in activity induced by a 2.7 mT static magnetic field in snail Br neurons and found two opposite intrinsic mechanisms underlying the neuronal responses. Prina-Mello et al. (2005) found that static magnetic fields were associated with cell differentiation and found a certain association between cell differentiation and a constant magnetic field. Jiang et al. (2004) investigated the correlation between the excitation functions and external conditions. They found that the magnetic field elicited a negative excitation function value at a fi xed point of a nerve fi ber membrane, which can evoke an action potential. Additionally, according to a previous study addressing the effect of magnetic acupoint stimulation on free radical metabolism in rabbits, acupoint stimulation enhanced superoxide dismutase activity, inhibited free radicals, lowered serum lipid peroxide, and strengthened antioxidant capacity (Zhao et al., 2000). Therefore, the effects of magnetic fi elds on neurons as well as the role of acupuncture points have been veri fi ed in the fi elds of the cytology, cell biology, and biophysics. In an effort to further understand the mechanisms and applicability of magnetic stimulation, this study measured electroencephalogram (EEG) signals in response to repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

Emerging, non-classical methods in EEG signal analysis and nonlinear-dynamics theory have attracted widespread interest. The complexity of an EEG signal re fl ects the degree of signal randomization. Previous studies addressing the complexity of EEG signals at different sleep stages showed that deeper sleep is accompanied by less complex EEG signals, indicating that brain activity is largely convergent during deep sleep (Meng et al., 1998). Thus, signal complexity is a measurable indicator for evaluating neural excitability. The vast majority of stimulation studies that attempt to regulate nerve function employ functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), while those that analyze EEG signals are virtually nonexistent. If we fi nd statistically signi fi cant differences after comparing changes in EEG signals after magnetic stimulation at true and sham acupoints, we can illustrate that magnetic stimulation at acupoints has a specific impact on EEG signals. Depending on the research purpose, different EEG indicators are appropriate. For example power spectrum analysis is a simple and reliable method for smooth EEG signals, nonlinear-dynamics indicators are necessary for analyzing non-stationary signals, and sample entropy is a simple, reliable, highly precise algorithm for complexity that has been effectively applied to the classi fi cation of EEG signals.

The Guangming (GB37) point is a vision-related acupoint that is related to blepharitis, refractive error, night blindness, optic atrophy, and other diseases (WHO, 2008). Previous hemodynamic studies demonstrated that occipital cortex responds to stimulation at the Guangming (Cho et al., 1998; Gareus et al., 2002; Kong et al., 2009; Li et al., 2003). Because this phenomenon is known and apparently reliable, we selected Guangming as the target for magnetic stimulation. Thus, to search for scientific evidence that magnetic stimulation alters brain activity, we conducted several experiments. First, we examined changes in sample entropy (SampEn; a nonlinear dynamics index) of EEG signals after magnetic stimulation was given at the Guangming and mock points in healthy people. Next, we looked at differences in SampEn values after visual stimulation given either before or after magnetic stimulation at the Guangming point. We studied EEGs under these conditions because in Chinese medicine the Guangming point is known to be related to visual function, and thus changes in visually-evoked EEG signals after magnetic stimulation at Guangming could verify whether magnetic stimulation there can affect visual function.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects and facilities

The experiment was performed at Province-Ministry Joint Key Laboratory of Electromagnetic Field and Electrical Apparatus Reliability at Hebei University of Technology in Tianjin, China from March to June, 2013. Ten right-handed subjects (6 male; average age: 26.5 years; range: 20–33 years) participated in the study and comprised students and faculty. They were recruited through a network registration and volunteered to participate in this experiment. All subjects signed informed consent prior to the experimentation. Subjects were included only if they were (1) in good physical and mental health, (2) were well rested, and (3) had no history of mental illness.

The experiment was performed without environmental stimuli or interference. The laboratory was in a quiet, temperature-controlled environment with good ventilation. Subjects indicated they were relaxed and not anxious before the experiment. Sweating and noise were avoided.

Guangmingand mock points

Guangming is a vision-related point, belonging to the Gall Bladder Channel of Foot-Shaoyang, and is located laterally on human legs, 5 cun above the lateral malleolus tip, at the anterior margin of the fi bula (Maciocia, 2005). The control condition consisted of magnetic stimulation at a mock point (a non-acupoint lateral location on the leg). Figure 1 shows the location of the Guangming and mock points.

Magnetic stimulator

rTMS was conducted with a Magstim Rapid2 magnetic stimulator (Magstim Company, Whitland, Carmarthenshire, UK) with the coil arranged in a fi gure-eight formation to achieve accurate positioning (Yang et al., 2010). The inner and outer diameters of the 8-shaped coil were 53 and 73 mm, respectively. rTMS (2.0 T) was administered at an intensity of 0.8 times the maximum central intensity at a fi xed frequency of 1 Hz.

EEG system

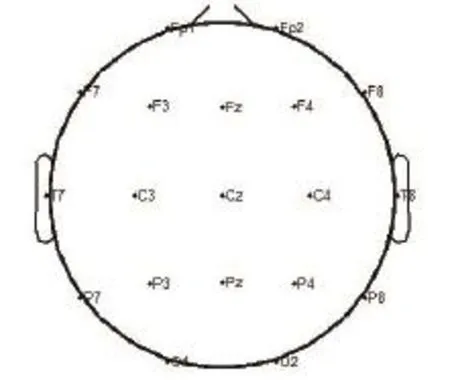

A 128-lead EEG recording and analysis system (NeuroScan Company, Charlotte, NC, USA) was used to record 64 lead EEG signals, with post aurem and mastoid (M1, M2) as a reference electrode, and a sampling frequency of 1,000 Hz. We selected 64-channel data, and distributed 19 channels evenly over the scalp (Figure 2). We chose 19 channels to meet the requirements of Scan 4.3.2 software (NeuroScan, Charlotte, NC, USA) and the EEGlab Toolkit (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), which were used to plot the EEG signal sample-entropy map.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the Guangming and mock points.

Magnetic stimulation

EEG data were recorded under the following fi ve conditions. (A) Magnetic stimulation at the Guangming: the coil was placed 1 cm above the left Guangming point and stimulation was given for 3 minutes. (B) Magnetic stimulation at the mock point: the coil was placed 1 cm above the left mock point and stimulation was given for 3 minutes. (C) Visual stimulation before magnetic stimulation at the Guangming: participants were first subjected to a checkerboard reversal-stimulation for 3 minutes during which EEG data were recorded. (D) Visual stimulation during magnetic stimulation at the Guangming: The 3-minute checkerboard reversal-stimulation was conducted simultaneously with magnetic stimulation at the Guangming. (E) Visual stimulation after magnetic stimulation at the Guangming: The 3-minute checkerboard reversal-stimulation was carried out following magnetic stimulation at the Guangming, and EEG data were recorded. The interval between each condition was about 5 minutes. A longer interval was not possible because the conductive gel being used would dry and impact signal acquisition. All subjects participated in each of the fi ve conditions.

EEG signal analysis

EEG signal preprocessing

Scan4.3.2 software provided with the NeuroScan 128-channel EEG analyzer was used for offline data preprocessing. The processing fl owchart is shown in Figure 3.

Sample entropy analysis

Figure 2 Distribution of the 19 channels used to plot the electroencephalogram signal sample-entropy map.

In 1991, approximate entropy was introduced to quantify the amount of regularity and unpredictability in time-series fluctuations (Pincus, 1991). Approximate entropy requires small amounts of data and is less in fl uenced by system noise, thus it is suitable for both random and stable signals. However, because both deterministic and random components are involved in biological signals, a bias in approximate entropy can be caused by self-matches. Sample entropy is a refinement of approximate entropy, a measurement introduced by Richman et al. (2000), which does not include self-matches. It is simpler and more accurate than approximate entropy, and requires approximately one-half the amount of time to calculate. A smaller sample-entropy value indicates lower complexity and more self-similarity. Practically, a relatively small data set is required for a rough estimate of sample entropy. In terms of analyzing mixed signals that consist of random and deterministic components, sample entropy is better than simple descriptive statistics such as the mean, variance, and standard deviation. Additionally, sample entropy does not require coarse-grained original signals, and is thereby particularly suitable for the analysis of biological signals (Zhang et al., 2009). In this study, we selected the value of sample entropy as eigenvalues of EEG data obtained from magnetic stimulation at the Guangming, and drew a sample entropy diagram based on EEG mapping to compare brain activity under magnetic stimulation at different points.

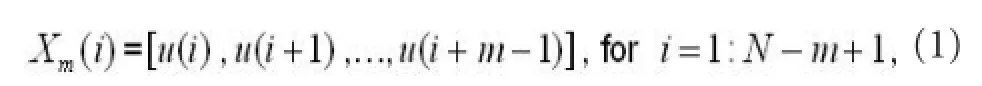

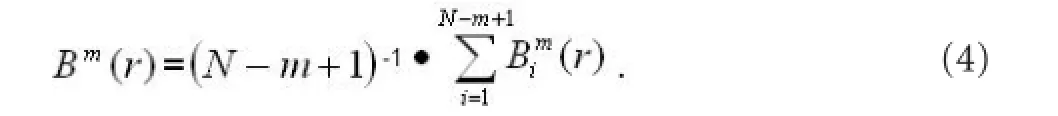

We processed the data as follows: For a time series of N points, the initial data were set as follows.

Step 1: A group of m dimensional vectors were formed such that:

where Xm(i) represents the vector of m data points from u(i) to u(i+m–1).

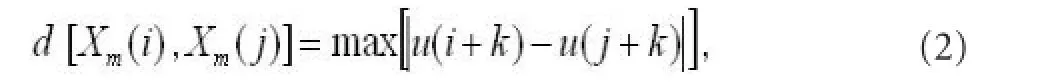

Step 2: The distance between Xm(i) and Xm(j) was de fi ned as

where k = 0 : m–1; i, j = 1: N–m+1, and i ≠ j

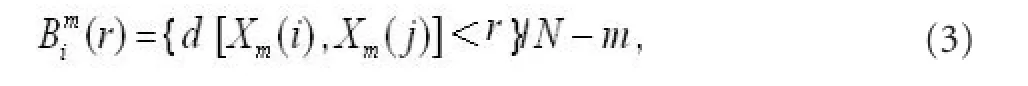

Step 3: Tolerance for accepting matches was de fi ned as r, the function for i ≤ N–m+1 was de fi ned as

and the mean value corresponding to i was calculated as

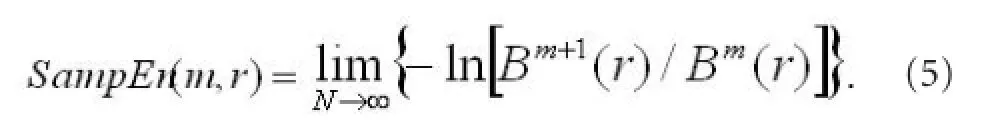

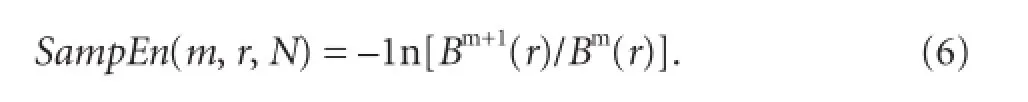

Step 4: To form a group of m+1 dimensional vectors, steps 2 and 3 were repeated to obtain Bim+1(r). Then, the mean value corresponding to all “i”s was calculated to obtain Bm+1(r). Step 5: Theoretically, we de fi ned sample entropy as

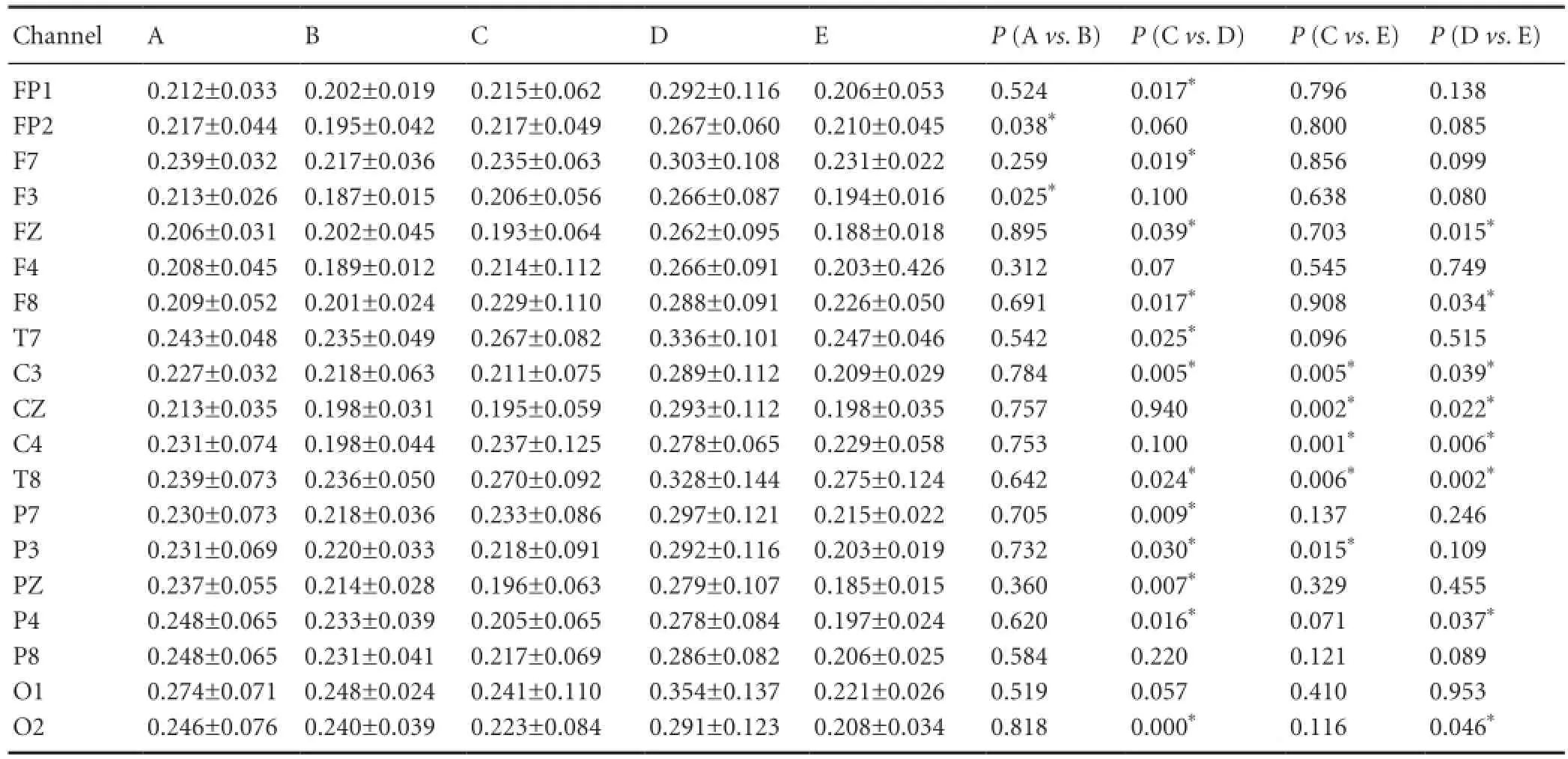

Table 1 Differences in mean sample entropy values of electroencephalogram signals between conditions

When N is a fi nite value, we can obtain the estimated value of SampEn, that is,

Where m is an embedding dimension, which is the length of sequences to be compared. Generally, m and r in the sample entropy algorithm are the same as those in approximate entropy, that is, m = 1 or m = 2, and r ranges from 0.1 to 0.25 of δ (δ is the standard deviation of the raw data). N is the data length, and often ranges from 100 to 5,000 to reduce artifacts. In this study, we used the value of m = 2 , r = 0.2δ, and N = 5,000.

Statistical analysis

Measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD and all data were normally distributed. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Paired t-tests were conducted to test for statistical differences between sample entropy under different conditions. A P < 0.05 was considered signi fi cant difference.

Results

Quantitative analysis of subjects

EEG raw data extracted from 10 experimental subjects were preprocessed as described above (removal of electrooculogram artifacts, baseline correction, and fi ltering). Data from two subjects were excluded because data from two channels were identical. This may have been because of excess injection of the conductive paste. Thus, data from eight subjects were used for statistical analysis.

Comparison of sample entropy values between conditions A and B

Mean sample entropy values from the eight subjects under conditions A and B were calculated, and then differences were statistically analyzed using SPSS 13.0 software. The data from 19 channels are shown in Table 1. Sample entropy values obtained from the right frontal electrode (FP2) and left frontal electrode (F3) were significantly higher under condition A than under condition B (P < 0.05), while no differences were found at other channels (Figure 4, upper left).

Comparison of sample entropy values between conditions C, D, and E

After data preprocessing, there were 80 cycles of single-channel time series for each condition, and each cycle was 80 s long (totally 80,000 data points). Sample entropy values from the EEG signals of eight subjects were calculated under conditions C, D, and E. Five-thousand data points were de-fi ned as a segment, with 16 segments were used to calculate sample entropy values at each channel. Then, the mean value was calculated for each condition and was analyzed using SPSS 13.0 software. Mean sample entropy values from the 19 channels under conditions C, D, and E are shown in Table 1.

Figure 4 Schematic diagram of the electroencephalogram measurement channels.

Comparison of conditions C and D yielded P-values (PCvs.D) that were significantly different in most channels, and distributed evenly. The number of channels exhibiting signi ficant or non-signi fi cant differences was similar (paired t-test, P < 0.05; Figure 4b). PDvs.Ewas also significant in several channels (overlapping somewhat with PCvs.D) with a widespread distribution (Figure 4c). However, the comparison between conditions D and E yielded fewer channels with signi fi cant differences than the comparison between C and D did. The most important comparison among conditions C, D, and E was between conditions C and E, with differences in sample entropies representing the effect of magnetic stimulation at the Guangming on EEG responses to visual stimulation. As the PCvs.Evalues shown in Table 1 indicate, EEG signals at the majority of electrodes were not different between conditions C and E, and signi fi cant differences were found only at C3, C4, CZ, T8, and P3. These fi ve electrodes were distributed in the parietal cortex, central gyrus, and right temporal lobe (Figure 4d).

Discussion

In this study, we compared sample entropy values of EEGs generated after magnetically stimulating the Guangming (condition A) or a mock point (condition B), and sample entropy values of visually-evoked EEGs before magnetic stimulation at Guangming (condition C), during magnetic stimulation at Guangming (condition D), and after magnetic stimulation at Guangming (condition E). Comparison between conditions A and B allowed us to examine differences in EEG complexity after magnetic stimulation at the Guangming or a mock point. We eliminated the impact of somatosensation, and found differences in EEG complexity that can be attributed solely to the location of stimulation. Signi fi cant differences between conditions A and B were seen in channels FP2 and F3, which are located in the frontal cortex. This suggests that brain activity in frontal regions underwent changes after magnetic stimulation that were speci fi c to the location of stimulation. This result is consistent with fi ndings described previously (Guan et al., 2008), showing that acupuncture at Guangming or a mock point led to differential activation of the frontal lobe. The sample entropy values in channels FP2 and F3 were generally higher during stimulation at the Guangming than at the mock point, indicating higher EEG complexity after acupoint stimulation. Magnetic stimulation at Guangming may therefore raise cortical neuronal activity.

Under conditions C, D, and E, we compared the changes in EEG signals when magnetic stimulation was delivered at the Guangming before, during, or after visual stimulation. Here, despite an uneven distribution, many channels differed signi fi cantly depending on whether visual stimulation was before or during magnetic stimulation. Similarly, many channels differed signi fi cantly depending on whether visual stimulation occurred during or after magnetic stimulation. Many channels exhibited significant differences that were widely distributed on the scalp. A focus of this study was to compare EEG signal complexity before and after magnetic stimulation at Guangming (between conditions C and E). The comparison between conditions C and E allows us to explore how visually evoked EEG signals are affected by magnetic stimulation at Guangming. While most PCEvalues were not signi fi cant, those at channels C3, C4, CZ, T8, and P3 were. This suggests that in response to visual stimulation, EEG complexity in the parietal cortex, central gyrus, and right temporal lobe is affected by prior magnetic stimulation at the Guangming, and that the effect may be delayed. Although the Guangming is an acupoint related to visual function, magnetic stimulation at Guangming in this study did not alter EEG patterns in primary visual (occipital) cortex. Effects observed in the parietal cortex, central gyrus, and the right temporal lobe, suggest that magnetic stimulation at the Guangming primarily affects somatosensory and auditory functions (Gareus et al., 2002). This may be why subjects complained of numbness and hearing voices during the stimulation. This study did not fi nd evidence that magnetic stimulation at Guangming can evoke changes in EEGs, which is somewhat similar to fMRI study of acupuncture stimulation at Guangming (Gareus et al., 2002).

In this study, we explored the effects of magnetic stimu-lation at Guangming on the sample entropy of EEG signals, and found that magnetic stimulation at Guangming had an impact on EEG complexity. Variation in sample entropy is a suitable measure to distinguish EEG signals under different physiological conditions. We selected points related to visual function as the target of stimulation because changes in EEG activity after visual stimulation are well known and easy to observe. Furthermore, understanding vision-related acupoints will help understand visually evoked EEG signals. To date, many studies have confirmed the association between acupoints and activity of specific brain regions, but experimental conclusions are controversial. Improvement in experimental and analytic methods is therefore necessary. Experimental fi ndings will guide the application of magnetic stimulation in clinical treatment, nerve rehabilitation, and neural regeneration. In this study, a weak spasm that differed individually was visible after magnetic stimulation at the mock point. This phenomenon indicates that magnetic stimulation at a mock point can activate motor muscles, and efforts to eliminate this phenomenon should be undertaken to improve experimental methods.

Acknowledgments:We would like to thank Professor Xu GZ, Professor Yang S and Lecturer Yu HL from Province-Ministry Joint Key Laboratory of Electromagnetic Field and Electrical Apparatus Reliability, Hebei University of Technology for providing experimental equipments and technical supports.

Author contributions:Zhang X collected and analyzed experimental data. Fu LD designed and implemented the study. Geng YH was responsible for the study concept and design. Zhai X performed data analysis. Liu YH was responsible for statistical analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Con fl icts of interest:None declared.

Peer review:This study aims to observe the effect of repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation on healthy people through a sample entropy analysis of electroencephalogram signals. Additionally, we compared electroencephalogram signals in response to visual stimulation before, during, and after repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming using nonlinear dynamics. The results showed that, repeated-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation at the Guangming has an apparent effect on the electroencephalogram signals, which confirms the contribution of magnetic stimulation.

Cho Z, Chung S, Jones J, Park J, Park H, Lee H, Wong E, Min B (1998) New fi ndings of the correlation between acupoints and corresponding brain cortices using functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:2670.

Gareus IK, Lacour M, Schulte AC, Hennig J (2002) Is there a BOLD response of the visual cortex on stimulation of the vision-related acupoint GB 37? J Magn Reson Imaging 15:227-232.

Gerhardt von B, Bailey P (1925) The Neocortex of Macaca Mulatta, Champaign: The University of Illinois Press, USA.

Guan YQ, Yang XZ (2008) Brain BOLD-fMRI study of electroacupuncture stimulating the acupoint related visual. Hebei Zhongyi 30:1065-1069.

Jiang CZ, Wang H, Wang J, Zhang L (2004) Activating function of peripheral nerve fi ber under the magnetic stimulation. Tianjin Daxue Xuebao 37:810-814.

Jiang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Dong Y, Dong Y, Xiang X, Bai L, Tian J, Wu L, Han J (2013) Manipulation of and sustained effects on the human brain induced by different modalities of acupuncture: an fMRI study. PLoS One 8:e66815.

Kong J, Kaptchuk T, Webb J, Kong J, Sasaki Y, Polich G, Vangel M, Kwong K, Rosen B, Gollub R (2009) Functional neuroanatomical investigation of vision related acupuncturepoint speci fi city: a multisession fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 30:38-46.

Kong T, Fan T, Han X , Guo Z , Lei L, Zang J (1993) Electroacupuncture promots the regeneration of different fi bers in rat’ tibial nerve. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 18:232-235.

Li G, Cheng LJ, Lin L (2009) Effects of static magnetic fi elds on characteristics of neuron delayed rectifier potassium channel. Tianjin Daxue Xuebao 42:923-928.

Li G, Cheng L, Qiao X, Lin L (2010) Characteristics of delayed recti fi er potassium channels exposed to 3 mT static magnetic field. IEEE Trans Magn 46:2635-2638.

Li G, Cheng L, Lin L, Qiao X, Zeng R (2009) Characteristics of neuron sodium channel exposed to 30 mT static magnetic fi eld. Guangdianzi: jiguang 20:1695-1698.

Li G, Cheung R, Ma Q, Yang E (2003) Visual cortical activationson fMRI upon stimulation of the vision-implicated acupoints. Neuroreport 14:669.

Maciocia G (1989) The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone, USA.

Meng X, Shao J, Ou YK (1998) Applying complexity of EEG signals to the states of sleeping. Shandong Shengwu Yixue Gongcheng 17:4-8.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1997) Acupuncture: Consensus Development Conference Statement. NIH Consens Statement 15:1-13.

Prina-Mello A (2005) Static magnetic field effects on cells. A possible road to cell differentiation. NSTI Nanotechnology Conference and Trade Show-NSTI Nanotech Technical Proceedings. Nanotech 1:96-99. Pincus SM (1991) Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:2297-2301.

Richman JS, Moorman JR (2000) Physiological time series analysis using biological signals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278:2039-2049.

Spasic S, Nikolic Lj, Mutavdzic D, ?aponjic J (2011) Independent complexity patterns in single neuron activity induced by static magnetic fi eld. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 104:212-218.

Wang Z, Che P, Du J, Ha B, Yarema KJ (2010) Static magnetic field exposure reproduces cellular effects of the parkinson’s disease drug candidate ZM241385. PLoS One 5:e13883.

World Health Organization (2008) General Guidelines for Acupuncture Point Locations, WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations in the Western Paci fi c Region.

Yu HL, Xu GZ, Yang S, Zhou Q, Wan XW, Li WW, Xie X (2011) Activation of cerebral cortex evoked by magnetic stimulation at acupuncture point. IEEE Trans Magn 47:3052-3055.

Yang S, Xu GZ, Wang L, Geng YH, Yu HL, Yang QX (2010) Circular coil array model for transcranial magnetic stimulation. IEEE Trans Appl Supercond 20:829-833.

You Y, Bai L, Dai R, Xue T, Zhong C, Feng Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Tian J (2011) Differential neural responses to acupuncture revealed by MEG using wavelet-based time-frequency analysis: a pilot study. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011:7099-7102.

Ya ZM, Wang JH, Li YZ, Tan YH (2000) Effects of acupuncture on mRNA expression for nerve growth factor during facial nerve regeneration. Zhonghua Wuliyixue yu Kangfu Yixue Zazhi 22:157-159.

Zhao DY, Fu Y, Li HL (2000) Magnetic acupoint stimulation on free radical metabolism of rabbit. Zhongguo Yixue Wulixue Zazhi 17:59-60.

Zhang X, Xu GZ, Yang S (2009) Complexity analysis of EEG under magnetic stimulation at acupoint of Zusanli (ST36). Zhongguo Shengwuyixue Gongcheng Xuebao 28:620-623.

Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Glielmi CB, Li L, Hu X, Wang X, Han J, Zhang J, Cui C, Fang J (2013) Long-duration transcutaneous electric acupoint stimulation alters small-world brain functional networks. J Magn Reson Imaging 31:1105-1111.

Copyedited by Phillips A, Norman C, Wang J, Yang Y, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

10.4103/1673-5374.130082

Yuehua Geng, Ph.D., Province-Ministry Joint Key Laboratory of Electromagnetic Field and Electrical Apparatus Reliability, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin 300130, China, 2522625@qq.com.

http://www.nrronline.org/

Accepted: 2014-01-19

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Acrylamide exposure impairs blood-cerebrospinal fl uid barrier function

- Preconditioning crush increases the survival rate of motor neurons after spinal root avulsion

- Adaptive and regulatory mechanisms in aged rats with postoperative cognitive dysfunction

- Increased expression of Notch1 in temporal lobe epilepsy: animal models and clinical evidence

- Transient axonal glycoprotein-1 induces apoptosisrelated gene expression without triggering apoptosis in U251 glioma cells

- Negative regulation of miRNA-9 on oligodendrocyte lineage gene 1 during hypoxic-ischemic brain damage